- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Page 21

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Read online

Page 21

As her skill progressed, Roz found herself called out at night by various midwives. They would rap on the thin siding that enclosed her drafty room. “I’se birthin’ twins tonight, Peep. You wants to come?” or “Dose little white hands might come in useful.” Gradually, they let her do normal deliveries, then trickier ones.

One damp night as they rode in the back of a wagon from a routine birth, Beulah shared some of the secrets of the midwives’ trade. A misty rain fell, making their veils limp and heavy, as they put their heads close together to talk. The father, already daddy to nine youngsters—this made ten—sat half asleep behind the mules who found their own way into town.

“Women wear out birthin’ so many. Here in my bag, I gots some seeds from de Queen Anne lace plant. It don’t grow so well here, but my cousin sends me jars of ’em from Nort’ Carolina. Woman take a spoonful of seeds wit’ warm water after she been wit’ a man, won’t no baby take. And dis here bottle, gots ergot of wheat. It can speed up a birthin’ or bring off an unwanted chile. Can kill de mother if you not careful.”

“Wouldn’t it be better just to recommend rubbers?” Roz whispered, appalled.

“Priests speak against ’em. Men don’t like to use ’em. Womens has gots to look out fo’ demselves, Peep. Don’t you be tellin’no white doctor what I jus’ say.”

“Never,” she swore.

In class, Nurse Emory spoke of spontaneous abortions, their causes, and the treatment of the women who suffered from them. Roz lingered behind after the lecture. “What about women who try to kill their babies in the womb?”

“Technically, this is a crime committed by both the mother and the person who supplied her with a drug or performed the surgery. Mostly, people keep quiet about abortions unless the baby was born alive and killed afterwards. Then, it’s murder, of course. You need to assess the situation. If a woman won’t hold or nurse her baby, you might want to suggest she give you the infant to take to one of the orphans’ homes. A lot of tragedy can be prevented that way.”

“Are these cases frequent, then?”

“Not among the Cajuns. They tend to force young couples who got carried away to the altar or raise the bastard within the family. You do see it among the Negroes with too many children to support, and more and more among desperate college girls. The upper crust isn’t immune, though they’re more likely to send a pregnant daughter on a long visit to an auntie in another state. Six months later, the girl comes back fresh as a daisy to marry as she should.”

Nurse Emory, seeing all her students but Roz gone, took a pack of cigarettes from a drawer in the table and offered one. Roz shook her head, but the nurse lit up and took a long drag.

“Bad habit. I picked it up in France while I nursed the war wounded. You know, plenty of incest occurs in the back country and in-breeding that leads to terrible birth defects. It would be better for all concerned if abortion was legal, but I won’t live to see the day. There’s not a woman in this class except you that can’t bring on a miscarriage with some kind of poison she stirs up. You stay away from that shit, or you’ll lose your license before you get it. Understand?”

“Understood.”

****

The brief month of February seemed to pass by in minutes rather than days. March, usually a time of warmth and blossoms, began cold and wet. Nurse Emory announced a day’s recess for the celebration of Mardi Gras and said she didn’t want to see any hungover students straggling in on Ash Wednesday. The midwives laughed and adjourned to enjoy their holiday.

Roz had no plans other than to sleep late and study her textbook. The teachers went back to their hometowns for the celebration. Even Mr. Toomey had been invited to the home of one of his sisters for a party. The Widow Perdue might have fallen on hard times when her husband died, but she maintained social connections with the better families in town and received an invitation to the bal masque which André and Loretta would, no doubt, attend. While brushing off her best black dress with its jet beading, the widow told Roz she wouldn’t be cooking today, but she was sure a pretty girl like Rosamond would have other places to go. Roz shrugged.

“My many invitations must have been mislaid.”

“Oh my! Let’s watch the parade together from the porch then, before I leave for luncheon with my friends. If you want to mask, I have trunks of old clothes in the attic you are welcome to use.”

The attic selection was not inspiring, mostly black dresses outgrown in size over many decades of mourning and small garments that must have belonged to the widow’s son as a baby. Roz shook out a bodice of black taffeta. Small buttons ran up the front from the waist to a high collar between rows of ruffles that ended just under the chin. A matching skirt that draped across the front and pulled into a small bustle in the back completed the outfit. She could squeeze into the costume without a corset, thanks to sparse rations and late night midwifery.

In her room, she slicked her hair back with pomade, inserted a tortoise shell comb high on the back of her head, and draped her Spanish shawl over it. Roz hoped the shawl would hide the fact that she hadn’t been to the beauty parlor in months. Usually hidden by her headdress, her hair hung in an unfashionably long half platinum and half golden blonde cascade of waves down to her shoulders. She tied it back into a small knot at her nape. For the finishing touch, she clipped a spray of seven sisters roses from the trellis in the yard and tucked it behind her ear. With stark white makeup, red lips, and darkened brows, Roz thought she resembled a ghost from the past century.

Sitting on a rocker waiting for the parade, she drew stares from by-passers and gave them a languid wave. Most of the adults weren’t costumed but accompanied children who had dressed up like bunnies or kittens. Henri and his pals came along wearing their version of wild Indian garb—fringed vests made from brown paper bags with crayoned designs of eagles and arrowheads, headdresses of multicolored construction paper feathers, and lots of war paint filched from their sisters’ cosmetic cases. One fat, one tall, and one small Indian carrying an umbrella perched on the front steps of the boarding house, keeping company with Roz and the widow.

The parade, when it came, was brief. The king’s mule-drawn float approached with the sugar planter, stuffed into white hose, golden knee breeches, brocaded vest, and a powdered wig. He waved his scepter from his throne. Little boy pages in purple velvet doled out glass beads and handfuls of candy to any friends they recognized.

The queen’s float followed with the maids settled on pastel pedestals like fancy iced cakes in a bakery window. They, too, flung necklaces sparingly as if the cheap junk were real treasure. Among them, Roz saw Verna Harkrider’s big-nosed, black-haired daughter who had been passed over in favor of a young woman bearing a strong resemblance to Clara Bow, the It Girl. Evidently, the queen had “It,” while Dottie Harkrider did not.

The last two floats brought the boys to their feet. Tubbs grabbed Henri’s umbrella, inverted it, and charged down the sidewalk shouting, “Throw me something, mister!” On these conveyances, the Rotarians vied with the Kiwanis for the generosity of their throws and the spectacle of their costumes carrying out the theme of “Circus of Delight.”

A tall, stooped ringmaster in a top hat and crooked handlebar moustache slung a cluster of beads up on to the porch where they skittered to Roz’s feet. She draped them around her neck. Beside the ringmaster, an Indian elephant trainer in black face and a bejeweled turban took more throws from his animal hook and tossed them into Tubbs’ umbrella. The same man pitched additional fake jewels to the boarding house ladies. Roz squinted. Could it be Cousin André? Both men were too tall to be Pierre.

The floats overflowed with clowns and strongmen in leopard skins and padded tights. A dapper young man dressed as a trapeze artist resembled Denny DeVille, but Roz doubted that Yale gave vacation days for Mardi Gras. He had to be a brother. A Fat Lady with a red wig and polka dot dress leaned over to shower candy on the boys and nearly fell off the float. Wally Brossard, Roz guessed, because most of

his bulk was certainly real. His float also seemed well-supplied with beverages of an illegal nature and a surfeit of sweets. If Pierre rode among the maskers, she hadn’t discovered his identity.

The parade passed, and the boys ran off in its wake, hoping to catch more throws. The widow excused herself for her luncheon date and left Roz on the porch alone. As she stood to go in and take off her stifling outfit, she glanced across the street, and there he stood, Pierre in a dark suit, white shirt, black tie, and carrying his medical bag. He crossed against tide of people following the floats and dodging mule dung, and met her on the porch.

“A senorita again?” he asked.

“A reformed gypsy.” Roz gestured to her long sleeves, high collar, tight-laced bodice, and ankle-covering skirt.

“A pity,” he said.

“I’m sorry I can’t invite you in. It’s against house rules.”

“I understand, but I have come to invite you out.”

“Moi? A married lady—or perhaps, a merry widow judging by the color of my gown. And who are you to ask me?”

“A well-meaning doctor inviting you to a family fete very well chaperoned.” He held up his black bag. “Unless, of course, you are going to the ball tonight.”

Roz cocked her head and laughed. “The courier with my invitation must have been waylaid by bandits. Yours as well?”

“No, the Harkriders made sure I got invited, but I declined as none of my family was going to be there. You’ll have to change and put your grand airs aside. We’ll be eating boiled crawfish with our fingers.”

“The best invitation I’ve had. Let me put on other clothes. Wait here.”

Roz rooted through her trunk and found nothing suitable for eating messy foods. Still in a quandary, she washed off her grotesque makeup and reapplied the lightest touches of pink lipstick and rouge. She could do nothing about her hideous hair. She hid what she could beneath a green cloche hat with a rolled brim, but a rim of platinum curls escaped all the way around. Well, she could always claim she masked as Harpo Marx. She’d seen him and his brothers do their act on the vaudeville stage at the Crescent. All she needed was a horn to chase the women. Sighing, Roz put on the hated red and green plaid dress from last Christmas. At least, it wouldn’t show stains, and she didn’t care if she spilled on it. Her black stockings and pumps would have to do. Pierre awaited.

They talked shop as they drove along. Pierre kept his hands on the wheel and his eyes on the road as they passed cane growing tall and spindly in the wet weather. Roz told him of interesting deliveries. He countered with his latest cases.

When Roz let her mind go astray to last year’s Mardi Gras, she wanted to scream for their loss of intimacy and the possibility of love. If Pierre had driven into the cane fields and pulled her into the backseat of his Ford, she would have been just as willing to throw up her skirts as she had been in the French Quarter. Nurse Emory’s stern voice lecturing on the need for good moral character among midwives sounded in her mind and ruined the memory.

Pierre saw her eyes stray to the dark lanes among the canes. In his teen years, he had taken more than one loose country girl into the fields for a romp. His Papa boxed his ears and told him to take his needs to a lady of the evening because that’s why prostitutes existed—to keep good women pure. He knew what Papa would say if he took up with a married woman of a certain reputation. “Find a nice girl and settle down, Pierre. Den you forget all about her.” Not likely. His hands itched to turn up one of the farm lanes, but he forged ahead on the main road.

He kept the conversation formal and professional until they came to a large, unpainted cypress board home set up off the ground on crumbling piles of brick. Behind the house, the bayou spilled over its banks into a grove of cypress trees, but in the front yard, the puddles had been filled with straw to keep down the mud. Black buggies parked beside Model T’s, both cars and trucks. The carriage horses turned out into an adjoining pasture hung their heads over the fence hoping for a chunk of turnip or lump of brown sugar from the hands of a dozen small children running wild among the vehicles. Pierre honked the Ford’s horn to warn the swarm as he parked on the end of the row.

He stripped off his coat and tie before leaving the auto. Taking her elbow, Pierre steadied Roz as her heels sank in the sodden yard. Three men perched on the outside staircase leading up to the traditional garconniere where Pierre had slept with his six brothers, raised their fruit jars of clear liquid and shouted out, “Eh, Pierre! Quelle est la jolie blonde, ti-frere?”

“My brothers, Odon, Euclide, and Ursin. Clovis, Minos, and Zenon are probably out back,” Pierre told Roz.

“How did you get the ordinary name of Pierre?” she teased.

“Born on his saint’s day, but don’t forget my middle name is Boniface.”

“Close call for you.”

Two of the men were older versions of Pierre more poorly dressed and showing the lines of outdoor work in their faces. Ursin, however, was broad and fat, and displayed his hairy arms without modesty.

“I brought a friend from the clinic,” Pierre answered in English as they approached the porch. “Roz Boylan.”

In rapid Cajun French, the loudest of the three, Ursin, asked if his little brother was sleeping with the pretty woman. Roz answered for him. She hadn’t spent hours in Sr. Marie Claire’s French class making up salacious phrases out of boredom for nothing.

“No, he isn’t.” Roz smiled. At least, one man here didn’t think she looked like Harpo Marx.

Switching to English, the mouthy brother jibed, “What’s da matter wit’ you, ti-frere? You sick? You got the syphy-lis?”

Like a cannonball shot from the front door, Alida Landry crossed her front porch and thwacked her eldest son on the forearm with a large, wooden cooking spoon. “You don’t talk dat way in front of da bebes, no, Ursin!”

Ursin licked the brown splotch that landed just below his rolled up shirtsleeve. “Bon roux, Mama.”

“Ha! You don’t buy me off wit’ dat.” Madame Landry came off the porch, took Pierre’s face in her hands, and kissed both his cheeks. “Mon bon fils.”

She looked over her son’s shoulder with hard eyes at Roz and whispered in his ear just loud enough for the girl to hear, “Maybe she da one got syphy-lis, a fast girl like dat.”

Roz hadn’t blushed when bantering with the brothers, but she did now. She wanted to turn and go back to the car when spare Simon Landry ran out of the house with his arms open. “Bienvenu! Bienvenu, Rosamond Boylan.”

He kissed her cheek. “I never miss a chance to kiss a pretty girl, me. Clovis, he late wit’ da crawfish, but you come inside. We got chicken gumbo and turtle soup on da stove to keep you ’til we eat. Alida, she makin’ beignets to use up da fat before Lent.”

“I’m afraid I’m one guest too many.”

“No, no! We just add more rice to da pot. Come.”

Pierre cocked his head at his father. His Papa winked. Maybe he would have given his son different advice from the lecture Pierre had imagined.

Simon Landry took his guest’s arm and escorted her to the crowded kitchen built on to the back of the house. Most of the women bustling around appeared to be in some stage of pregnancy, and Roz was hard put to separate Pierre’s sisters from his sisters-in-law.

Alida, scowling, had returned to her beignet making, turning over square pillows of dough in an iron pot filled with boiling lard. A bunch of hungry children waited for the batch to be lifted from the oil. As their grandmother drained the doughnuts, small hands reached up and were slapped away with an admonition to wait ’til they cooled. An older girl cranked a large flour sifter full of 10-X sugar over the beignets, and another carried the plate to a long plank table with benches on both sides. The flock followed.

Pierre sat two toddlers on his lap to make a space for himself and Roz at the table.

“Café brulot?” one of the women about six months along offered, holding up the pot. Roz thought it might be his sister, Collette—or was

she the one in her fourth month wearing the blue dress?

“Yes, thank you.” The sister passed a red enameled cup to her. Roz took a sip of scalding coffee brewed with caramelized sugar water. “C’est bon!”

“Here, you try dis.” Simon Landry squeezed between the bellies of the women with a small bowl in his hand. “Odon, he caught a big tortue in da bayou last week and keep her alive ’til just dis morning, him.”

Roz spooned up the rich brown turtle soup. “Wonderful, just like our cook used to make—no, it’s better.”

Another bowl passed her way before she finished the first. “Try my gumbo,” insisted a nursing mother holding her infant up to a swollen breast. That one might be Matilde, Euclide’s wife. Roz wasn’t sure.

She sipped the soup in its thin Cajun roux, missing the thick okra base of New Orleans style gumbo. The chicken was tender and the andouille sausage spicy. “Very good, but could I have the filé powder? I’m used to it being thicker.”

“You make dat slimy okra kind where you come from?”

Roz started to say she’d never made gumbo, but she was saved from this confession by the arrival of Clovis and the crawfish. People spilled out of the kitchen on to the long back lawn sloping toward the swollen bayou. Adolescent boys tended two metal pots full of boiling water hung over open fires.

“Da water in da Basin, she high. Lost some of my traps, but I t’ink we got enough to stretch dis feast.” Clovis set down two enormous burlap sacks that throbbed with live crawfish.

“Now we cookin’.” Simon tossed fresh dug and scrubbed red potatoes into each pot and laid on the spices—garlic cloves, and small onions, handfuls of salt, a whole box of cayenne pepper, and lemons split in two with his clasp knife. Testing a spud for doneness, the old man signaled to Clovis who upended the first sack into one of the pots. A few lucky mudbug survivors who fell outside the kettle scrambled for the bayou, but they were scooped up by small boys who used the snapping claws of the crawfish to terrorize their sisters. Mothers shouted in both French and English to their children not to run so close to the fire.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

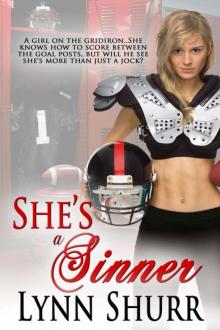

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner