- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Page 20

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Read online

Page 20

“Let me pay you. Is twenty dollars enough?’ He took two bills from the money clip in his pants pocket and handed one to each woman.

“I heard you delivered a fine baby boy to Roscoe and Maisie as well. Roscoe’s granddaddy is my yardman. I gave them that cabin when I heard the girl was expecting. It’s not much, but they had nothing. If they owe you, I’d be happy to pay your fee.”

“This plenty, suh. I ’preciates it.”

It astonished Roz to see Midwife Senegal obviously shaken by this largesse. As for herself, she wanted to go right out and buy a big rare steak. Visions of the placenta resting in the china bowl crossed her mind. Well, maybe a nice roasted chicken would be better, but she wanted to eat the whole thing herself. Many hours had passed with nothing but coffee since the peanut butter crackers at lunch. Still, she felt exhilarated.

The front door slammed, and footsteps sounded rapidly up the stairs and down the hall. Pierre Landry appeared in the doorway to the birth room.

“I’m too late, I see. It looks like the midwives have taken care of the matter, but let me examine mother and baby as a precaution. Mr. LeBlanc, if you’d step out for a moment. Ladies, please stay.”

“Afterbirth in dat bowl. It gots a tear.”

“I see. I’ll check to make sure we’ve got it all,” the doctor said as he worked beneath the blanket. “Bleeding has stopped. Very good work.”

Dr. Landry lifted the sleeping baby from the arms of the mother who barely stirred. So gently the child didn’t wake, he listened to her heart and lungs and checked the reflexes of her feet and hands.

“Small but strong. Ladies, I’m going to speak to the father out in the hall if you would finish cleaning up in here. Merci.”

“Ain’t dat always the way,” grumbled Beulah. “But Doc Landry ain’t so bad. He know where he come from.”

The bedroom door opened again to make way for Netta who pushed an elaborate cradle hung on a graceful wheeled stand to the bedside. The maid placed the infant on lacy sheets and pulled a veil of netting close around. Though the open door, the women could hear the doctor giving instructions to Mr. LeBlanc.

“I’d prefer not to do a transfusion at this point. Let your wife rest. See that she gets plenty of fluids—beef bouillon would be good—and anything she wants to eat to rebuild her blood. I’ll come back late this afternoon to see how she’s doing, but unless she suffers a fever or lethargy, I’d rather not move her to the clinic. I can see she’ll have the best of care here and will probably be more comfortable in her own bed.”

“Thank you so much.” The grateful father pressed another twenty-dollar bill into the doctor’s hands.

“This is much more than my usual fee, Mr. LeBlanc. Really, all I did was check the work of the midwives.”

“My wife is priceless to me.” Seeing the midwives about to leave, he called out, “Cook is up. She will make y’all a breakfast. Miz Beulah, just go on down to the kitchen. I’ll have Netta set a place for the lady and Dr. Landry in the dining room.”

“I need to get back to the clinic for early rounds, but thank you. Roz, I mean Midwife Boylan, would you like a ride back into town?”

“No, thank you, Dr. Landry. I do believe I would like some breakfast. Don’t set a special place for me, Mr. LeBlanc. The kitchen will be fine.” With that, Roz followed Beulah’s broad backside down the stairs to the rear of the house.

The cook appeared to know the midwife, and the two talked the whole time she prepared the breakfast, though she seemed a little uneasy about the white lady waiting for food. Beulah recounted the story of the birth, giving Roz credit where it was due, and telling the cook what foods the new mother should have for building the blood and nursing if she wanted.

“Cook all her meals in iron pots, you hear. She need red meat. No strong greens, no onions or garlic. It give de baby colic.”

The cook fried up ham slices and forked them on to thick yellow plates. She stirred the redeye gravy and poured it out over the heap of grits next to the meat. Two fried eggs with the yolks done perfectly for mixing with the grits followed. Even as the women ate, the spread kept increasing with fluffy biscuits, crisp toast, fig preserves and orange marmalade. Slices of pound cake were added just in case they didn’t have enough to fill them.

“Mr. LeBlanc was a surprise. He could be the French woman’s father. There must be a story about them,” Roz said as she tucked into her eggs, breaking the yolks and blending them with the grits and gravy.

“Sho’ is. People still talkin’ about how old A.A. went off to be a soldier in de Great War when he near forty and still not married. He come home wit’ dat bit o’ French fluff, and peoples still doan know what to make of her. Maybe she jus’ wanted to get out of Paris. But LeBlancs, dey always marry out of the parish.” Beulah lowered her voice even more. “They gots black blood in de family, and everybody in town know it.”

“Mr. LeBlanc certainly doesn’t look it.”

“It from way back. One old granny midwife told me so. Some long ago LeBlanc took a quadroon chile for his own. Dis family tainted, white folks say.”

“People do like to talk whether they know the truth or not. I don’t believe it.” Roz cut off a chunk of ham and chewed.

“Whoa, Peep. For a little thang, you sure can eat,” Beulah observed.

“To be honest, I haven’t had a meal this good since I left the St. Rochelles.” Roz crammed a biscuit dripping with butter and preserves into her mouth. “I’m always late getting up for class and mostly have just bread and syrup in the mornings.”

“Well, midwifin’ do raise the appetite. Say, Peep, why you don’t go back to de clinic wit’ Doc Landry? Every single white lady in town want a ride in his car, know what I mean?” Beulah gave her a wink.

“I am still a married woman, as the doctor reminded me a short time ago, Midwife Senegal. And, my Mama always said, ‘You come home from the dance with the one who brought you’.”

Roz looked down at her shoes splattered with blood and birth fluids and sighed. “One more thing, I’ll never wear these pumps to a soiree again.”

Chapter Twenty-Eight

By the second week of classes all the midwives could predict that if one of them was fetched for a delivery, Rosamond Boylan would jump to her feet and ask to come along. An undertone of black voices would murmur, “Peep, Peep, Peep,” quickly quelled by a stern look from Nurse Emory.

“I’m allowing Mrs. Boylan to accompany you because you have a wealth of practical experience to share. I might add she is well ahead of the class in book knowledge. There is no playing favorites here.”

“It okay.” Beulah Senegal spread her big bottom in the space Roz left behind. “She didn’t faint nor nuttin’ when she went wit’ me. Even knows how to swaddle a baby now, and dose little hands of hers come in handy.”

“Very well then. Class we shall discuss determining pregnancy and due dates today.”

“Seems babies come when dey wants,” said a thick-bodied yellow woman in the second row.

“True, only three percent of births actually occur on the due date, but a date gives the mother a comforting goal, and the midwife the knowledge that a baby may be long overdue and in need of induction. What is induction?”

“Bringing da baby on,” said a woman wearing a white sunbonnet.

“Rupturing the membrane surgically,” shouted Roz as she followed Granny Sue out the door. A chorus of Peeps followed her, but she took it good-naturedly. After all, she was going to assist with another delivery.

****

Twelfth night came. In New Orleans, Roz would have been attending parties where the names of the new queens of Mardi Gras were announced. Instead, she jumped out of the back of a rickety truck that held a sack with two laying hens. She’d already turned down the offer of a live chicken in exchange for any eggs it might produce in the future.

The delivery, the tenth for the woman concerned, had gone swiftly and easily, and Roz arrived back at the boarding house in ti

me for dinner. A large cardboard box across his knees, Henri waited on the doorstep.

“Mama said I should bring this to you. It came in on the mail boat. She said your mama thought it might be stolen if it was left at the boarding house. What do you think it is?”

“I have no idea. I wasn’t expecting anything this big, just some papers.”

“Oh, this came, too.” Henri pulled a large legal envelope out of his sweater. “Ain’t you gonna open the box?”

Instead, Roz ripped off the top of the envelope containing her separation papers from Buster. They had been filed the second day of January. By this time next year, she would be free of Burke Boylan forever. She gave Henri a dazzling smile.

“So, what’s in the box?” the boy persisted.

Roz tugged on the strings tied around the cardboard. When they failed to budge, Henri took out a dull pocketknife and sawed away until the wrappings split.

“Finally got your knife, Henri?”

“I won it from Tubbs on a bet. He said I was too chicken to climb to the top of the live oak in his yard and jump, but I did. Don’t tell Mama.”

“Oh, Henri, you are so like me. Doesn’t your mama ever say ‘If your friends jumped off a bridge, would you do it, too?’”

“All the time. It’s a cake!” the boy shouted as Roz parted some tissue and a layer of waxed paper.

A ring of King Cake dressed in all its gaudy green, purple, and gold sugar glory sat in the box. Roz lifted it out on its flat of cardboard and set it between them. “Cut yourself a piece, Henri, and one for me, too. After you finish ruining your dinner, you’d better go home. Your mother will worry if you stay too long.”

“She worries about you, too.”

“I know.”

Loretta and Ethel constantly sent over odds and ends for her room and small offerings of food. Cousin André, whether still angry over the New Year’s Eve debacle, or embarrassed about the niggardly allowance he doled out to her, usually greeted Roz aloofly on the street and hurried away.

Henri licked the last of the frosting from his fingers and raced off. “Thanks for the cake, Cousin Roz.”

Roz carried the rest of the treat inside and gave it to Widow Perdue for the night’s dessert. She anticipated a good meal. The widow had Roz’s share of the sweet potatoes being candied in a cast iron pan. Turnips greens with chunks of the vegetable enfolded boiled in a neighboring pot. Cornbread cooled off to one side of the stove. The ever-present thin-sliced ham waited on its platter. Roz had parlayed her “fee” from helping with Maisie’s delivery into another rent reduction, and she still got to eat it.

Widow Purdue eyed the cake. “I suppose you’ll want another dollar off your rent for that?”

“No, I want to share it with the others. We can have a Twelfth Night party just like in the city. It’s a little stale, though.”

“We’ll warm it just a bit, but not enough to melt the frosting. Take out the cornbread and call the others.”

As usual, the others didn’t need to be called. In January, the roads were bad and the water was high, higher than usual, so drummers were scarce, and none sat at the table tonight. Edna and Faye slipped into their seats, and Mr. Toomey held his utensils at ready.

They plied the widow with compliments on the candied sweet potatoes, and she, flattered, promised she’d make a pie out of the rest of the yams. As Roz cut the King Cake, Miz Purdue surprised everyone by taking her good cordial glasses from the breakfront and pouring portions of her own cherry bounce from a dusty jug that looked like it had been involved in fermentation for a year.

“It’s not really liquor, you know,” the widow assured them. “Just a little hobby of mine. I make it for medicinal purposes.”

“My mama used to make this,” Bernard Toomey said nostalgically.

The drink made Roz feel a longing, too, for a speakeasy in the French Quarter. How wild cherries soaked in sugar and illicit whiskey and left to ferment couldn’t be liquor, Roz didn’t question. Both the cake and the jug went around a second time. Faye bit into her piece of pastry and winced. “There’s something in here, a bean or a stone.”

She spit the object out into her hand. She held a silver charm shaped like a rose. “Oh, this must be for you, Roz.”

“No, no! It means you are Queen for a day, and the rest of us must do as we’re told.”

“Really?” Faye’s gingery eyebrows raised with possibilities. She looked across the table at Bernard Toomey. “Mr. Toomey, loosen your collar and take off your coat.”

“In the presence of ladies?” he questioned.

“You are going to be my court jester and amuse me while Roz paints my toenails with some of her fancy polish. Edna, you can do my nails. Miz Purdue, keep the wine coming.”

Roz brought not only the nail polish from her room, but her Mardi Gras crown, packed, certainly, to remind her of who she was.

“Is it pure gold?” Faye marveled.

“Plate, I’m positive, but fit for a queen. I crown you Queen Faye, Mistress of Revels.”

To everyone’s amazement, Bernard Toomey turned out to be a good jester. First, he licked a spoon and hung it off the end of his nose, then recited the inspirational poem, Invectus, which suddenly became very funny. He called for vinegar, baking soda, and a basin of water, and made a little boat from a piece of the evening newspaper. When he fueled the paper boat with the vinegar and soda, it puttered around the basin on its own power. The women applauded.

“It’s all science, the magic of chemistry,” he said modestly.

As the jug of cherry bounce reached its bottom, Bernard sang a fair but maudlin rendition of When Irish Eyes Were Shining and followed it up with an attempt at a jig. Feet tangling, he ended up on the floor next to Queen Faye’s cherry-colored nails. He kissed each toe. The cherry color spread over the schoolteacher’s entire body, obliterating her freckles as it rose.

“Lovely toesies,” Bernard murmured as he finished with the last little piggy.

Roz expected the widow to call the evening at an end, as it seemed to be going in a strange direction, but Miz Purdue slept soundly in the chair where she’d been sitting since she brought out a second jug of wine. Edna dozed face down on the table, and her own head buzzed.

“With your permission, Queen Faye, I think I’ll call it a night. I have class in the morning.” Roz pushed unsteadily out of her chair and wobbled off to bed. As Twelfth Night parties went, this one had been better than most.

****

Roz, Edna, Faye, and Mr. Toomey had no more parties for the remainder of the Mardi Gras season. They got up the next morning with cherry bounce headaches and went about earning or learning for a living. Edna refought the War Between the States with her history students. Faye taught the Romantic Movement in her English class. Mr. Toomey tightened his tie and tested on the periodic table.

The Kiwanis and Rotary Clubs selected the king of Chapelle’s Mardi Gras from amongst their members. King Louis XVI would be portrayed by a prominent sugar planter, the local paper announced with no secrecy about it. The article revealed his Queen Marie Antoinette as the daughter of a local judge. Verna Harkrider told anyone who would listen that the queen should have been her Dorothy, but old Queen Bagasse, the wife of the king, was jealous of her Dottie’s beauty.

Even the midwives had a chuckle over the feud. “That girl, Dottie, she jus’ plain ugly. They put her in the court so she has to wear a mask.”

“Why does Verna keep referring to the judge’s wife as Queen Bagasse?” Roz asked.

The women threw back their heads and laughed some more. “Peep, the bagasse is what’s left after all the sweet juice done been squeezed out the sugarcane.”

“I believe that could apply to Verna as well,” she answered. No one disagreed.

Roz gave no more thought to Mardi Gras. She applied herself to learning the stages of pregnancy and fetal development, the progress of labor, and the warning signs of eclampsia, recognition of venereal diseases, and a host of othe

r subjects that would horrify her mother.

She practiced delivery on an anatomical model and marveled at the experienced midwives’ ability to turn a badly positioned baby for birth. They showed her their techniques for coaxing along a breach birth and pushing an infant determined to be born butt first back into the womb until the head presented. Nurse Emory hovered all the while, reminding them again and again to call the doctor if complications occurred.

Best of all, the women allowed Roz to accompany them to birthings. They had begun to refer to her as the only chick in a coop full of old hens—Beulah Senegal summed it up.

“Not many wantin’ to learn our trade anymore, Peep. Everybody want a doctor now, even po’ people. My own daughters, dey wants to be nurses. I keep tellin’ ’em, times ain’t changed that much. See de colored men come back from de Great War? What dey do over there? Not fight, most of ’em. Dey dug ditches and drove mules same as here. In a hospital, my girls be scrubbing floors and cleanin’ bed pans.”

“Someday, things will be different. More and more women are working now,” Roz told them.

“Negro women have always worked, Peep. It don’t make no difference.”

“One day it will,” Nurse Emory said crisply. “That is why you must be the best at what you do. Class, come to order.”

During the lunch break when Nurse Emory had gone for her smoke, the women gossiped about their instructor. She was the granddaughter of an abolitionist lady who had come down after the War to teach black children to read and write. That fine person married into one of the oldest planter families in the area. They owned their own island and all. The do-gooder New England bride passed on her beliefs to her children and grandchildren to the ruination of the Emory family, many of the white folks thought. Nurse Emory might be starchy, but her heart beat in the right place under her spotless white uniform.

Roz soaked up all the information she was given, the most attentive student in class. Though when she heard Pierre’s voice in the coffee room, her mind strayed. She was always whipped back to the present by a pointed question from the nurse who missed nothing.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

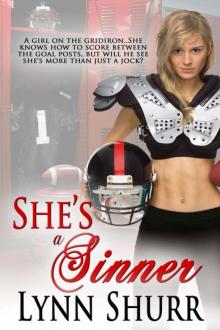

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner