- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Mardi Gras Madness Page 9

Mardi Gras Madness Read online

Page 9

“They can’t stay, Miss Lola. I’m sure about that.”

Laura escaped into her apartment finding she had forgotten to lock it in her haste to join the LeBlancs. Even the French doors stood open as if an invitation for ice cream addled her brain. Snake had made a mess of the sewing basket and scrap cloth and as if evading a scolding, tried to ingratiate himself by winding around Angelle’s legs. The girl threw an empty spool for the kitten and became engrossed in play, the grown-up world fading for her.

“Since we have become dispensable, the armoire is in here.”

Laura moved to her bedroom. David’s old shirt lay draped on the bed, and she knew Robert LeBlanc had taken notice of it. She threw open the doors of the armoire quickly.

“Look, ‘C.S.’ I am sure this is a genuine Celestin Segura cabinet.” She ran her fingers over the initials carved in the honey-colored wood.

“I think you’re right. Despite what I said about antiques, I did take an interest in the black Seguras at one time in my life. This is fine work. Should be in a museum, or at least out at my place.”

“Mrs. Domengeaux doesn’t want to sell. I just thought you would be interested.”

“Because of old stories?”

Deciding not to be a total hypocrite and feign, “A story? What story?” Laura replied, “No, not at all. Something that happened so long ago should have no bearing on the present or the future.”

“But it does. Was this your husband?” Robert pointed to the wedding picture. The man was becoming dangerously serious. Laura sat on the edge of her bed and tried to break his gaze.

“Yes,” she answered without elaboration.

“What you do about your life from now on will always be affected by a man who is as dead and gone as Celestin Segura. Whether you marry or not, have children or not, will depend on how much he influences your future.”

“I think that is very cold and uncalled for.” Laura’s hand stroked the comfortable, soft texture of David’s old shirt.

“Listen, I have a point to make. I first heard the story of Marie Segura and Aurelien LeBlanc when I turned thirteen. Maybe Pearl told me, but it might have been before she came back from California. Funny, I can’t recall who told me. Everyone in Chapelle knew the story except for me, it seemed, and talked about it behind my back. I kept thinking if the babies had not been switched, I might have been out there in the fields planting cane, watching my own relative, the great Judge LeBlanc surveying his arpents on horseback.

“I know it isn’t likely. The black Seguras were craftsmen, and nearly white. They say Pearl’s sister went to California and married a white man. That’s why no one ever hears of her. Now days, it wouldn’t matter much, but in her youth, passing meant giving up your family. As for myself, I would have been a member of the black elite, the high yellows, the almost white. But at thirteen, all I could see were the cane workers, their sweat for my profit, their shacks for my big white mansion. That old story became an obsession for me.”

“I refused to honor family tradition and study law at Tulane. To my father’s horror, I took agricultural courses at the state university. After he died, I switched our land from cane to cattle. There is more dignity in raising cattle, but much less money.

“I followed in my family’s footsteps in only one way. I married out of the parish. I really believed no one in Chapelle would have me and never tried to find out. I brought home a girl from New Orleans who turned out to be my very distant cousin. We met at a fraternity party and found out we had Caroline Montleon in common.” Robert smiled ruefully and studied the picture of David with his sandy hair and light eyes.

“That gave me my pickup line, ‘Vivien Montleon, I have a Montleon somewhere in my family tree—we must be kissing cousins.’ Clever opening, don’t you think? I neglected to tell her about Marie Segura. When Vivien became thoroughly enchanted with my big plantation, my waving stands of cane and my father, the judge, I got her pregnant. Not exactly an accident on either side. I thought this way she’d be mine forever and would never leave me, even when she heard what people said about the LeBlancs of Chapelle. Later, much later, I found out she thought she had tricked me into marriage and deeply regretted her success. So did I. Would you, knowing the stories?”

Laura, listening intently, aware he had shut the bedroom door to prevent Angelle from hearing, found herself unprepared for the question and mistook his meaning.

“I don’t know. I’m not ready to make that kind of a decision yet.” She clutched David’s shirt to her chest.

“That was a rhetorical question, not a proposal. Perhaps I should have gone into law. I have just made my point. The past does matter. You cannot escape it. It can ruin lives.”

Laura wanted to offer this bitter man, who usually covered his feelings with a smile and a joke, some comfort, some hope, but the right words would not come. Dropping David’s shirt, she reached out a hand to him, but he turned before she could touch his arm and opened the door.

They spotted Angelle playing with Snake on the old balcony. The child’s father crossed the room in three strides and pulled his daughter to his side.

“That’s a poor place to play, Angelle.”

Laura, just behind him, murmured, “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I should have locked the door.”

“She’s not your problem, Mrs. Dickinson. Come on, Angelle. It’s too late. We’ll catch it from Tante Lil if we aren’t home for dinner.”

As they moved to leave, Angelle returned to her old theme. “I could make you come to stay with us. I could.” Her father pushed her ahead to the doorway. The group collided with Lola Domengeaux carrying a large enameled pot up the narrow stairs.

“Leaving so soon? I was bringing up dis nice gumbo for dinner. Stay a while, why don’t you?”

“It’s too late, Mrs. D,” Laura said. “They need to get back to their place.”

Chapter Nine

Devoid even of students in panicked search of report material this late Friday afternoon, the Ste. Jeanne Parish Library might as well have closed an hour early. Ruby Senegal conscientiously entered new titles into the computer while Laura made work for herself weeding shelves of forty-year-old Avalon romances with laughably dated cover art of nurses in old-fashioned caps and horror stricken maidens teetering on the brink of a cliff.

This make-work gave Miss Lilliane the freedom to nap in the office—as she often did without Laura’s aggravating presence to keep her aroused. The new librarian noticed the rusted pickup truck parked in the bookmobile drive. Angelle, who had been absent from the library all week, wiggled restlessly in her father’s shadow in the cab. Inhaling in preparation for the uncomfortable moment that had to come someday, Laura went out through the garage.

Smiling, she hoped not woodenly, she went directly to the driver’s side of the truck to confront the man who had confided in her and received nothing in return. She began the conversation as casually as possible.

“Hello there. We’ve missed Angelle this week. Will you be bringing her to the bonfire and storytelling tomorrow night?”

“No. She’s going to spend the weekend with her grandparents in New Orleans. Her mother is home from the spa again and should be by to pick her up any time now.”

“I’m sick,” Angelle interrupted, kicking at the dashboard of her father’s truck with one sneakered foot.

“You got away with that story this morning with Pearl, young lady, but not with me. Now put your feet back where they belong.”

“It’s hot in here,” the child whined.

“Come inside, please. Angelle can wait with me and have a cold drink. There’s coffee, too,” Laura offered, finding herself in the conspiracy of adults against a difficult child again.

“I want to get back to the ranch. Thanks anyway. Angelle, get out and wait with Miss Laura.”

When the child made no move to open the door, her father leaned over and opened it for her, giving the little girl a slight shove that dislodged her in Laura’s directi

on.

Laura caught the child’s hand and reached up for an overnight bag almost as scratched and battered as the pickup truck.

“I appreciate this,” Robert Leblanc said as he handed over the suitcase.

Laura waited for one of his characteristic smiles and received none. Looking grim, he backed from the drive as soon as Laura and Angelle stood clear.

“I’ll tell you what, Angelle. Why don’t you run over to Domengeaux’s and buy a sack of Miss Lola’s pralines for your trip. I’ll bet your mother would like some.”

“No way. She never eats candy because she’s afraid she’ll get fat. But I’ll get some for us.”

“Look, I’ll give you my apartment key, too. Would you run upstairs and see if Snake has enough water? It’s such a hot day for October.” Laura led the child inside and managed to retrieve her purse from a desk drawer in the office without disturbing Miss Lilliane’s nap.

“It’s always this hot in October,” Angelle commented as her babysitter rummaged for the apartment key and spare change.

“Not where I come from. Up north, we’d be getting ready for snow.”

“You don’t want to go back there, do you?”

Laura looked up from her search. Tears wet Angelle’s dark eyes. “Not for a long time, honey. Are you really sick?”

“No, ma’am. It’s just that it’s okay when Thurston comes in Grandpa’s car and takes me to New Orleans. He lets me sit in the front seat, and we stop for barbecue at this place only black people know about, and then we have purple snow cones for dessert. But when Mama comes, we have to go straight to the city. I’m not allowed to talk to Thurston or have anything sticky, and Mama only talks about herself and her diets and her headaches and her hairdresser. I hate her!”

“No, you don’t.” Laura rushed to refute this blasphemy of motherhood. “Maybe you just like being with your father better.”

“I do hate her. She didn’t want me, and I don’t want her. I want you.” The tears in Angelle’s eyes overflowed. She hugged Laura’s waist like a python suffocating its prey.

Laura, feeling as helpless as any woman unused to children, removed and caged Angelle’s hands around the door key and two dollar bills, then gave her a hug to send her on her way.

“Go get the candy and check on Snake. We’ll have a little party before your mother arrives, and you can pick out some books to read in the car.”

Angelle went, head hanging, her long, dark hair plastered against her pale cheeks with tears. Laura reheated some of the strong Cajun coffee, thinking she needed something more bracing, a drink or a tranquilizer, to cope with the LeBlanc family. Fortunately, the library offered none of these alternatives. In a while Angelle and her troubles would be on the way to New Orleans and a calmer weekend lay ahead.

When she moved to the window again to see if Angelle was on her way back, she noticed the silver Mercedes parked in the place Robert’s old truck had vacated. A uniformed chauffeur, a black man, lean and gray-headed, held the door for his mistress.

Vivien LeBlanc projected the epitome of elegance, slim to the point of emaciation, and pale to the extreme of ill-health. Her short, champagne blonde hair lay in feathered layers cut by some exclusive and overpriced hairdresser unknown to librarians, teachers, and other women who had to work for a living. The lady actually seemed to require assistance to exit from the car. She swung her long legs in model fashion, knees together, over the side of the seat and glided upwards with the help of the driver’s arm. Once he had his passenger on her feet, the chauffeur ran ahead to open the door of the library. Vivien LeBlanc followed in her Italian shoes with her pencil-thin heels tapping out the message on the sidewalk that she did not have to walk if she chose to ride. She entered the converted house as grandly as if she were checking into one of her spas for the weekend.

“So you’re the new librarian. About time they tossed the old witch out. I’m here for Angelle. Get her for me.”

Laura, who had grown used to the almost overwhelming friendliness of the Chapelle natives, had no witty retort, only the truth. “Angelle is at Domengeaux’s store. She’ll be back soon.”

“Thurston,” snapped the mistress. “Wait in the car. I must sit down. I have such a headache from the drive.”

Disliking the woman completely but determined to stay neutral, Laura offered coffee as well as a seat in the kitchenette area. The other staff members appeared to be needed at the front desk quite suddenly and vacated the area. Miss Lilliane slept on in the office.

“No coffee. We have a long drive ahead. I could use a cigarette, but I suppose librarians never smoke.”

“I don’t, but some do,” Laura replied, treading on the edge of politeness. “I believe Miss Lilliane could spare a cigarette.”

“Right. I forgot about the old bat and her nicotine habit.”

As Laura quietly entered the office and pilfered the aged librarian’s cache of menthol lights and matches, she gloated a little. Although clad in an expensive light blue suit and immaculately groomed, Vivien LeBlanc exhibited all the unpleasant signs of a heavy smoker. Robert’s former wife, though only a few years older than Laura, had small crow’s feet radiating from the corners of the pale blue eyes even the suit failed to color enough to make attractive. Hard lines surrounded her thin, pink-tinted lips. Yellow stained the teeth behind those lips. Her expensive clothes had a saturated odor of smoke about them Laura found repugnant. Feeling slightly superior, she surrendered the pack and matches into Vivien’s nervous, nicotine-stained fingers with their pearly manicured nails.

After she lit and drew deeply on a cigarette, Vivien slid the pack and the matches into the pocket of her suit and resumed tapping her enameled nails on the Formica of the table. “Where is that child? As I said, we have a long drive. I suppose I’ll have to go after her myself.”

She sent Laura an imperial look implying the younger woman should volunteer to fetch the girl, but Laura gave herself another surge of satisfaction by saying, “I’m sorry you have to leave so soon. Domengeaux’s is just up the street on the corner.”

“I know. I used to live in this godforsaken place. Say good-bye and thanks for smokes to the old hag and give all my love to Robert.” Vivien waved a pallid hand toward the office and stalked on her sharp heels toward the front of the building. Laura did not rush to hold the door for her.

A half hour later, Laura turned the key in the front lock, the last act of the library closing ritual. Sirens blasted the air, startling her. A few moments ago, this had been a routine Friday afternoon with the new librarian slamming doors and files with sufficient force to awaken the old librarian and tell her time to go. Without so much as a pleasant farewell, Miss Lilliane wheeled to her parking space shouting to the janitor for assistance. Closing duties, the one chore Miss Lilliane had relinquished without a fight. Half smiling at the abrupt departure of their old boss, the rest of the staff wished Laura a nice weekend and went on their way speculating about the location of the fire. The young librarian finished checking the stacks for loitering students or slumbering senior citizens, locked the rear doors behind her, and turned toward the shriek of the sirens.

With the volunteer fire department only a few doors from the library, the noise continued outrageously loud. Chief Fontenot’s chair in the shade where he spent most of his afternoons toppled as the fire chief heaved his large belly upwards, adjusted his suspenders and lumbered toward his red truck with the flashing light attached to the cab. His assistant, an agile man of forty who waited patiently through long boring days for the chief’s retirement, backed the small fire engine from the garage. Volunteers swarmed from neighborhood businesses, the earliest arrivals grabbing heavy slickers, boots and helmets from the hooks in the garage and leaping on to the side of the engine like fleas attacking a large red dog. Pickup trucks began congesting the streets and clusters of excited children clogged the sidewalks. No one had far to go for the show.

The smoke billowed from Domengeaux’s store. For a momen

t, Laura leaned against the library door for support. Had she left the stove on at lunch time? What did it matter now! She made herself move up the block to where Mrs. D stood wringing her white apron with her large hands.

“I don’t know what happened. I smelled smoke and called da chief. Myrtle Hill’s ringing da rest of da volunteers now. I…” Mrs. Domengeaux stopped talking abruptly as if the wind had been kicked from her belly. In fact, the entire crowd from overwrought small children to oldsters, who had been recounting the history of fires they’d witnessed in Chapelle, fell silent.

On the small balcony over the store’s awning stood Angelle LeBlanc clutching the black kitten. The cat clawed at the long sleeves of her white cotton blouse in its panic, but Angelle seemed frozen in the furnace of the fire. She stared with large dilated eyes into the fiery heart of the apartment through the closed French doors. The heat popped a pane of glass from the window frame. A flying shard slashed through the child’s thin blouse and drew blood. Angelle jerked but did not move. The frantic cat struggled free in the brief second the child’s grip loosened. Snake bounded from the balcony onto the awning beginning to smolder as cinders from the roof bit into the fabric. He leapt, landed on all four feet and shot toward his cool, remembered sanctuary beneath the church.

At last, the fire company acted. The earliest of the volunteers connected the hoses to a nearby hydrant, braced and sent spraying streams of water onto the roof and awning. Angelle’s white blouse clung to her small back and her black curls turned into wet snaky ringlets against the fabric. She stood completely still.

Chief Fontenot called to her, “Be right there, sugar. Now don’t you move,” as if Angelle had been thrashing in terror. The chief hoisted his bulk on to the second rung of a ladder resting against the building and steadied by his slimmer assistant. He moved slow, so slow that Laura wanted to tear him from the ladder and save the child by herself. She took a step forward, but Mrs. Domengeaux held her arm and a volunteer fireman pushed her back into the crowd. The hot bricks began to lose their grip on the rusted bolts of the old balcony. The metal bent and dropped a foot from the wall. Angelle fell with her back pressed against the ornate grillwork, but she did not move of her own accord.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

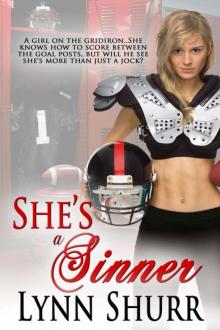

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner