- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Courir De Mardi Gras Page 6

Courir De Mardi Gras Read online

Page 6

“I have to get back to the office. Ya’ll have a nice visit with Suzanne.” Nodding to his hired historian, he said without expression, “Stop by the office if you want a ride home.”

Then, he deserted her in the midst of the battle. “Coward!” she wanted to shout after him. An unexpected ally appeared in the form of Sally. “Ya’ll want coffee now?”

“In the parlor, Sally,” Miss Letty indicated.

“Yes, in the parlor,” Miss Esme echoed, entirely recovered from her brief fit.

Evidently, the two old women adhered to the old code of not arguing in front of the servants. With a silent truce called, they retired to the parlor. Sally appeared with her tray and stood holding it while Suzanne took a demitasse and added sugar. Still, the servant continued standing right in front of her.

“Take a cookie,” she said in disgust, as if a Yankee didn’t know a thing about fine manners. Suzanne selected a gingersnap with a burnt bottom. Sally moved on to serve Miss Esme.

Miss Esme took her cup and cookie. “Sally has been with our family since she was fourteen. She still does all the cooking. Isn’t she a marvel?”

“Definitely,” Suzanne quickly agreed.

“Why, when Letty and I attended St. Joseph’s, she would bring our lunch to the school yard on hot days so we needn’t walk home in the heat and dust. It always came on a covered silver tray, cooling things like cucumber on bread and butter and a bucket of cold lemonade. She’d wait under the trees while we ate, then take the bucket and things back home.” Esme sighed over the good old days and nibbled at her charred cookie.

“Sally does the cooking because Esme never learned how. She was too genteel.” Miss Letty raised her cocktail sausage-sized pinkie in the air.

“You did learn to cook and look at you now!” Miss Esme counterattacked.

“Tell me about the historical marker,” Suzanne intervened. “I understand you are responsible for it.”

“Oh my, yes!” Miss Esme’s face filled with delight again. “We thought up the words, and Brother put up the money. Bronze casting is very costly, you know.”

“She left off Eli Jefferson and put in the yams,” Letty responded.

“It was too expensive to have both, and ‘yam’ is a shorter word than ‘Jefferson’, that’s all,” Miss Esme explained.

“Brother wouldn’t pay for ‘Jefferson’, you mean. Now I say when a feud is over one hundred fifty years old, it has got to stop. Why, Henry and I were just like Romeo and Juliet.”

“Big, fat Juliet, little, skinny Romeo,” Esme taunted like a schoolgirl. “Traitor to the family!”

“Now look here, Esme, I tried just as hard as you to get the name of this town changed to St. Julien.”

“But Georgie’s mother stopped us. What a terrible woman!” Miss Esme leaned confidentially toward Suzanne. The cuff of her pink polyester tunic took a dip in the coffee cup she held in trembling hands. “A disappointed woman.”

“Well, we were all disappointed in Jacques. We thought Nephew would come back from Vietnam covered with medals and follow in Victoir St. Julien’s footsteps. He looked so handsome in his naval officer’s uniform. All his brothers who hadn’t gone to college were just plain foot soldiers who got drafted. Jacques enlisted, but he went and brought home that woman from Virginia. The only thing she liked about this place was Magnolia Hill,” Miss Letty continued.

“Oh no!” cried Miss Esme. “She liked one other thing.” The sisters cackled like co-conspirators, both of them turning pink.

“Jacques was surely a womanizer. He seemed happy to spend his days living off the rents and investments and chasing skirts. Then, he’d go to Joe’s Lounge and drink and tell all about his conquests.”

“A trial to his family, a trial to his wife. Maybe that’s why she turned so mean,” Letty continued.

Suzanne wondered if Dr. Dumont knew about Jacques St. Julien’s reputation on his own turf.

“That’s just family talk. Women loved Jacques, and the men liked him, too. Wasn’t he elected Capitaine of the Courir de Mardi Gras when old Alonzo Guidry died? You say you and Henry wanted to end the feud. Jacques was the one who did it, I say. He drank with the Huvals and the Patouts and the Badeaux boys every night at the Lounge. They got along fine. I think Virginia turned ugly when they took out her female organs. That causes early change of life, you know,” Esme whispered. Suzanne did not contradict her.

Esme continued working on her theory. “Virginia Lee came here and found out she had married a ‘coonass.’ Forgive me, Letty. I hate that word, too. Cajun was bad enough, then people like the Jeffersons brought back ‘coonass’ from overseas after the war. We should be called Acadians as in that lovely poem, Evangeline by Longfellow,” she instructed Suzanne. “I always had my students read it and memorize the prologue. Are you familiar with the poem, my dear?”

“Eighth grade English. ‘List to a tale of love in Acadie, home of the happy.’ Yes, I am.” Suzanne suppressed a wince brought on by middle school memories of Miss Farrell cramming epic poetry into adolescent brains. Secretly, she loved the poem and doted on Romeo and Juliet, but who wanted to be teased? She could see Miss Esme gave her a gold star smile for her knowledge.

The former teacher went on talking. “Do you know, I never use the word nigger because I know how ugly words hurt?”

“That’s not what soured Virginia Lee. It was discovering when her money ran out she had to stop buying those fancy antiques because Jacques wouldn’t raise the colored folks’ rent or put anybody out of business. He just let things keep rolling downhill. And he slept with every woman he laid hands on except his wife.” Letty made her comment more graphic by snatching at her own large breasts straining the stretchy blue fabric of her top.

“Oh, Letty. You can be so crude. We have a guest here.”

“No one thinks anything of it now! Look at this young woman sleeping up at the Hill with Georgie, not a chaperone on the premises.”

“Well, they aren’t sleeping together. Georgie is such a good boy. He painted our house last fall.”

“How would you know? They could have met on one of his business trips. Maybe, this history thing is a hoax. He might be his father’s son in disguise.”

Suzanne finished her coffee in one gulp and rose. “Excuse me, but I have a lot of work to do at the house.”

“There, now you have embarrassed our guest, Letty.”

“Forgive me, my dear. Georgie is a nice boy, but let’s face it. All men are animals underneath. You just forget I said anything and do your job at the Hill.”

Suzanne accepted the apology gracefully, but still insisted she had to leave. Esme trailed her out on to the porch. “Do, do come again. For coffee. Please. Next week.”

“If I can,” she promised and started off along Front Street.

At a safe distance from the storm center, she slowed down and began to take in the scenery she’d missed on her headlong walk two hours before. Below the drawbridge on the opposite side of the river, a large hollow live oak stood, green in winter, but with a gap in its trunk large enough to hide a man. A stout knotted rope hung from its lowest branch out over the water. The rain-swollen bayou reached to within a foot of the rope, but she suspected in summer when children swung out over the river and played in the hollow, the water ran much lower. Beyond the tree, a house with a screened porch sat safely raised on its brick pilings. She took in the serenity of the scene and a deep breath of the mild January air. Acadie, home of the happy, indeed. The sun came out, brightening the bayou from a sullen gray to a pale, sparkling brown.

She continued down Front Street past Main and the Roadhouse still serving a few late diners. The warehouses beyond decayed by the bayou, the edges of their soft red bricks sloughing away into dust, their high, small-paned windows milky like cataracts or black and blind where young boys practiced rock throwing. Tucked among them, the infamous Joe’s Lounge flourished under a yellow neon sign hanging out over the street where the road turned to gravel.

Tempted, Suzanne opened its red metal door. Dark and abandoned at midday, midweek, a fat bartender washed glasses by the light of the beer signs.

She made her way to the bar through a maze of small tables with four upturned chairs crowning each one.

“Could I have a Coke, please? With plenty of ice.”

“Don’t you see dat sign, cher?”

Among the display of bottles fronting the mirror behind the bar, a taped message read, “No Ladies without Gents.”

“It keeps down da fights, you see. We ain’t one of dem city singles bars, no. If a guy brings a lady, well, we don’t ask do she come from a good home. But, no mother’s son ever come in here and got rolled if it wasn’t his own damn fault. On Fridays and Saturdays, we got da best Cajun music in da state. You get yourself a man, honey, and come back den. Be glad to serve you.”

“But no one else is in here, and I really need something to wash down my lunch. Please!”

He started moving his bulk around the bar as if he were going to bodily remove this annoying Yankee girl. Rolls of fat undulated softly beneath his Lite Beer T-shirt as he made headway. She tried another tack.

“You see, I’m doing research on Port Jefferson, and everyone said you have to go to Joe’s Lounge. They have the best bands in Louisiana. Are you Joe?”

“Me? No! Dere ain’t no Joe, no more.” The bartender’s big belly quivered with laughter as if she had tickled him in the stomach, but he stopped advancing. “Me, I’m Hypolite Huval. ‘Hippo’ people call me. Guess you can see why. I own dis place now. Used to have da Roadhouse, but one of da young Sonniers bought me out to fix it up fancy. Old Joe, he was ready to retire down by Grand Coteau wit’ his daughter, and I had to have me a place, so I bought him out. Bon, no? Old Joe’s been dead, I t’ink, since some time last year. You gonna put Joe’s Place in da city papers, cher?”

His pudgy fingers pulled on the soft drink tap and extracted an extra-large Coke onto half a glass of crushed ice. “On da house,” he said, pushing it toward Suzanne.

“Actually, I’m not with a newspaper. I’m staying up at Magnolia Hill while I prepare a booklet on the house and town.” She half expected the friendly Hippo to repossess the drink. “I understand Mr. Jacques St. Julien came here often.”

“Near every night. You be sure to mention dat. Here’s where da men meet to plan da Courir de Mardi Gras, and Jacques, he was da Capitaine.”

“Tell me about the Courir.”

“Well, I can’t. It’s a secret society like da Masons, you see. Womens ain’t supposed to know not’ing about it.”

“I understand.” She thought “male chauvinist pigs,” but didn’t say it.

“But you come back wit’ a date on Saturday night and dance. I always say, me, free drinks to anyone from da Hill, but George ain’t sociable like his daddy. He don’t even ride wit’ da Mardi Gras.”

“Then tell me about Jacques.” It would take a while to swill the Coke she’d begged. To leave after her victory seemed out of character for a journalist who was going to put Joe’s Lounge on the map.

“Oh, Jacques, he was da best of all da Capitaines in all my years. When he blew dat horn, all dose riders had better saddle up or he’d fight ’em, and he stayed sober so he could do dat. Mais cher, he let you have some fun, too. Sometime, he ride off wit’ one of da pretty girls on his horse. Da mamas would cry and pray ’til he brung her back, but dey was only gone jus’ a minute. Maybe he kiss her out around da barn, dat’s all. Rest of us do da Mardi Gras song and dance for da old and ugly ones to make ’em feel good. We have a little beer, chase da chicken for gumbo, and move on when Jacques tell us. He gallop us into town, stirring up dust and scaring dose old roosters, and we dance and eat and drink ’til midnight. Den, he make us all go to Mass.”

Hypolite sighed deeply. “Now dey want to let the womens ride. Man, dat’s da end of a real good time. I mean you could piss off da side of your horse, and everyone laughed. Can’t do dat wit’ womens along.”

Wondering why any female would want to ride, drink beer, and chase chickens all day, Suzanne almost sympathized, but her mother’s feminist upbringing held her back. How much more appealing to be carried off on a white horse for a kiss behind the barn than to be one of the boys, but to each her own. She finished enough of the enormous drink to be polite and said good-bye and thanks to Mr. Hippo who shouted after her, “Y’all come back Saturday.” Between coffee with the St. Julien sisters and Saturday night at Joe’s Lounge, her social calendar was certainly filling up.

She rounded off the afternoon by exploring another of the side streets, appropriately named St. Julien, running alongside the old basket maker’s shop. Behind the row of shops lay a pleasant residential strip of small white, blue, and pale yellow cottages. The road sloped gradually downward, the housing having less paint and more peeling the lower the street went. Trailers sat in the yards behind gray wooden shanties. She passed the Pilgrim Baptist Church with its one pane of stained glass shining like a ruby in the forehead of a Buddha over the narthex.

Suzanne experienced the same feeling of anxiety she might have if she’d wandered innocently into the black ghetto of Philadelphia, but no one threatened her. The elderly sat on porch steps or tended the remnants of their winter gardens. Tiny, dark children stared as she passed, but the elderly nodded pleasantly enough.

The sky clouded over again and grew as black as her surroundings. She had no desire to bring attention to herself by returning the same way she’d come, but St. Julien Street appeared to have no crossroads. The street transformed into a rural route where a few shabby lounges hugged a curve in the road.

Resigned, she crossed the street, and marched purposefully up the other side as if she were late for a very important engagement. Most of the children had gone inside when the weather threatened. She approached the Pilgrim Baptist Church when the deluge let loose. In moments, water cascading down the decline lapped over the low curbs. She shoved the parish history book under her top to protect it, but her shoes grew soggy. Her hair plastered to her skull in wet ringlets. She kept walking directly into the rain, back toward the security of Main Street. A woman, middle-aged and medium brown, hailed her from a screened porch where she sat watching the storm.

“Come on in, come on in! Get yourself out of that rain.”

Suzanne hesitated and then made her way up the walk and the three cinder block steps leading to the porch. Her hostess wore a brightly striped caftan over her ample body and covered her gray hair with a stiffly styled black wig.

“I saw you pass and wondered what would happen to you when the storm broke. It wasn’t likely you were visiting anyone on this end of town. Why, you looked as out of place as a crawfish in an oak tree. I saw that once back in the big flood. Come in and dry yourself. I’m Odette St. Julien.”

“Suzanne Hudson. Thank you for inviting me.”

“Just being Christian. Let me make you some hot mint tea. Take off those wet shoes and get a towel out of the bathroom to dry that hair.” She hesitated a moment, then suggested cautiously, “You could put on my robe hanging there on the peg. It’s clean. I have an electric dryer, and we could get the wet out of your clothes.”

Suzanne put on the warm, red flannel robe even though it wrapped twice around her and padded barefooted into the living room where she exchanged her dripping clothes for the cup of mint tea and a seat on the sofa. Despite the sagging porch and flaking paint that made Mrs. St. Julien’s home blend with the rest of the neighborhood, the interior was clean and cozy on this dreary day. A burnt orange area rug covered the gray linoleum of the floor, and a hand-knit afghan of umber, green, and yellow yarns fanned across the divan. A large single room air conditioner, not operating this moist January day, filled one window. An immense television took up most of the wall opposite the sofa.

The air conditioner served as a stand for potted plants: begonia slips wintering over in small clay pots; an avocado grown from seed in a Mexican jar; broad-leaved house plants set in ba

skets like the ones the old man wove. The television had its own burden of framed photos: large and small snapshots of children and grandchildren; a very tall young man in cap and gown; a couple with the bride in white lace, the groom in a tuxedo; and one that looked like a black and white publicity still of a sports figure kneeling by a basketball. She got caught examining them more closely when Mrs. St. Julien returned with her own cup of tea.

“There now. Let’s have our tea and talk while your things dry.”

She could hear the whir of the dryer and the clanking of the zipper of her jeans against the drum coming from the kitchen. The air smelled pleasantly of perfumed dryer sheets. She and her hostess settled comfortably on the sofa.

“You have a handsome family.” Suzanne nodded toward the framed pictures. She’d seen her activist mother do this countless times to set people at ease when she went out soliciting for her favorite charities. In this case, her daughter was the object of charity.

“My daughter, Harriet. My son, Lincoln.” Her hostess rose, gathered an armful of the photos and brought them to the coffee table where the teacups sat.

“They’re both school teachers. I’m a retired teacher myself. Harriet has two sons, and Linc, he got a boy on the fourth try. This is Linc and Doris on their wedding day. And these are my grandchildren.”

She handed Suzanne a multiple portrait frame stuffed with school and baby pictures. “Harriet’s boys, Ohin and Salim. Those names mean ‘chief’ and ‘peace’ in some African language. They laughed at me for naming them after Harriet Tubman and Abraham Lincoln. At least those people were Americans. And here’s Linc’s girls, Tiffany, Crystal, and Misty, and the baby, George Lincoln, Little Linc we call him. Here’s my boy when he played basketball for the NBA.” She showed the glossy still with obvious pride.

“Your son was the Lincoln St. Julien,” Suzanne said, mentally thanking Birdie for the information and trying to remember what NBA stood for, not that it mattered. The word basketball gave her the clue.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

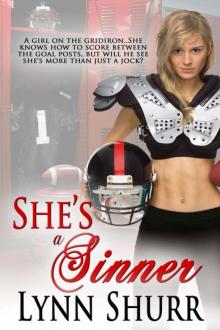

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner