- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Page 25

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Read online

Page 25

“Better not be no kitten in there. Cats, they can smother a new baby.”

“It’s not a kitten. The gift is this box of chocolates all the way from New Orleans. I believe new mothers should be pampered,” Roz continued in her starchiest manner. She hoped she sounded exactly like Nurse Emory, superior and undeniable.

“Better not be no puppy, neither. We got mo’ dogs around here then we needs.”

“Emmy Lou, who is at the door?” a high voice called from the parlor.

“Says she the midwife. Got a present for Miss Anaise.”

“For heaven’s sake, let her in. The draft alone is bad for the baby.” The woman whom Roz had last seen in hysterical tears came to the door. “I’m the child’s grandmother, Clarise Olivier. Do come in, but please limit your visit.”

Lowering her voice, Mrs. Olivier added, “Anaise needed surgery to deliver, you know. She’s still very weak and shouldn’t be exposed to germs. I’ll take you upstairs.”

Roz followed a pair of narrow hips and long legs remarkably like the daughter’s up a graceful spindled staircase. Clarise Olivier tapped on a door at the far end of the hall. “Are you awake, dear? You have a guest, the midwife who attended you.”

“Come in,” Anaise answered in a remarkably strong voice. She lay propped up in a feather bed old enough to have been used by Jefferson Davis, covered with lace-edged sheets and a half canopy of pale blue and gold. Little Lionel DeVille sucked vigorously at one of her plump, blue-veined breasts protruding from a quilted silk bed jacket edged with ecru lace. The elder Mrs. Olivier averted her eyes from the sight.

“How are you, Anaise? Any problems? Any questions I can answer? I see you did decide to nurse. Good for you.”

“Mama and Mother DeVille aren’t too happy about it. I had to ask one of the nurses at the clinic to show me what to do since neither mother breastfed. Did you bring me chocolates?” Anaise’s eyes turned greedy. “My appetite is simply voracious, and I feel sublime except for the sore tummy. They won’t let me out of bed. I do tire easily, but it’s nothing an afternoon nap won’t fix.”

“You look wonderful. Here.” Roz opened the golden box, selected a morsel topped with a candied violet, and popped it into the mouth of the nursing mother.

“Yummy!” Anaise DeVille plucked Lionel from one breast with a small pop and gave him the other before he could whine.

“Don’t eat too much at one time. Chocolate can have a laxative effect on babies.”

“I’ll try to restrain myself.”

“Well, then, I’ll let you two have a nice visit.” Mrs. Olivier twisted her fine-boned hands together. She couldn’t seem to take her dark and beautifully made-up eyes off the exposed breast that still dribbled milk. Finally, she handed Anaise an embroidered hankie and retreated from the room.

Anaise put the hankie over the leaking breast. “It is a messy business. Hector isn’t too pleased about having the baby in the room, either, though he couldn’t be prouder of his son—the next governor of Louisiana, he says—after the boy plays football for Tulane, of course.”

Roz nodded her understanding. Her father had said similar things about his lost sons. His girls were going to be queens of the Mardi Gras. She didn’t wish it on Roxie.

“Anaise, I need your help with a small problem.” Roz took a seat on a little gold and white boudoir chair and lifted the basket onto her lap.

“I delivered this child last night to one of the girls out at Broussard’s Barn.” Roz parted the covering so the tiny, delicate face and tight curls of the baby could be seen. “Her name is Innocent DeVille.”

Anaise’s glowing color drained from her face. “Is it Heck’s child? Did he betray me so soon?”

“No. I’m sorry I blurted it out that way. The baby belongs to Denny. The mother is colored, very light-skinned, barely eighteen. Her name is Kitty Brown. If I don’t do something fast, she’ll end up prostituting herself out at the Barn, and the child will have to go to the Children’s Home. The mayor must have influence with old Wally Broussard. Could you ask him to find them a place? Every socialite needs a good cause to support, my mother always said.”

“Couldn’t mine be eradicating polio or some other awful disease?” Anaise shifted Lionel to her shoulder and patted his back until he released a manly belch.

“Young women forced into prostitution because they had an illegitimate child are worse than a disease. And, you might do something for Eloise Elmo, too, while you’re at it. I think she’d like to get out of the business, but doesn’t know how.”

“How could I possibly help Eloise or this Kitty?”

“Didn’t you say your father-in-law and husband would give me anything I asked right after your son was born? Are you going back on that?”

“No, of course not. The Oliviers and the DeVilles never renege on a promise,” Anaise said with a hint of the old imperial attitude in her voice.

“Good. Then, here’s something that will help them to do the right thing. Dennis DeVille was named as the father of this child, and that’s the name I plan to file on the birth certificate. You know how gossip like this gets around in a small town. The sooner they settle Kitty and the baby elsewhere, the sooner the talk will die down. Now, I will leave Innocent here with you. There is a jar of formula and her nursing bottle in the basket. If you need more, call me.”

“That won’t be necessary. If the men balk, I’ll threaten to nurse the child myself. I bet they won’t be able to get out to the Barn fast enough to retrieve the mother.”

“Why, you cunning rebel, you. I can just see it now—The Anaise DeVille Home for Unwed Mothers.”

“How about the Anaise DeVille Sanctuary for Reformed Prostitutes?”

Roz threw back her head and laughed. The release of tension felt so good after the events of last evening. “That’s the spirit. Call if you need reinforcements.”

Roz left the DeVille mansion empty-handed. Feeling light and happy, she bounced along in her sensible white shoes and barely turned her head when a car stopped next to her. Pierre Landry leaned across the front seat and opened the door. “May I offer you a ride somewhere?”

“No. I’m only walking back to the boarding house, and the rain has stopped.”

“I thought you might need to take that baby you delivered last night over to the Children’s Home in Lafayette. I heard you cheated me out of a fee.”

“Already? My, word does spread fast in Chapelle. Who told you—your favorite hooker, Eloise?”

“Get in the car.”

“I think not. I have my reputation to consider.”

“Get in the car if you want an explanation.”

“No need to explain to me. Men have their needs is what I’ve always heard.”

Pierre glanced up and down the street, empty on this dreary April day. He lowered his voice. “Yes, they do, and I was taught early to take mine to the kind of woman who got paid to take care of them after Papa caught me with Susu Theriot. If her baby hadn’t been the image of Otto Muller when it was born, I might have been the youngest married man in all of Chapelle. As it was, I worked extra hard for Doc Spivey to earn a little pleasure money. As my mama said, any decent girl that gives it away is looking to trap a husband.”

“Is that so? Then, I couldn’t possibly ride with you. What would people say?”

“Forget I ever offered. Wally called me out to the Barn to examine the mother. He wanted to know when she would be fit to work.”

“I hope you told him never.”

“You did a good delivery, Roz. No tearing. No sign of infection.”

“The baby was small. I’m arranging a home for her and the mother.”

“That should cause a stir. The girls rarely escape from Broussard’s Barn. I gave Eloise train fare once, and she returned it to me when I was called out to set her broken arm. Be very careful, Roz.”

Roz shivered though the day wasn’t particularly cold. “I don’t think that’s in my nature, Pierre, but thanks for your concern.”

She slammed the door decisively and watched the doctor drive away without his knowing how much she had wanted to accept that ride.

Chapter Thirty-Two

Like a lady of leisure, Roz lay, fully dressed, on top of her covers taking an afternoon nap when a pounding fist nearly broke in her door. She scrambled for the little pistol she had unearthed from her trunk after talking to Pierre and pointed it at the door. Any second now, Bubba Broussard might smash the flimsy barrier off its hinges.

“Who’s there? What do you want?”

“Ursin. Ursin Landry. You come wit’ me right now. My woman say da baby, he comin’ quick quick.”

“Oh, Pierre’s brother. Doesn’t she want the doctor to do her delivery?” Relieved, Roz put down the gun.

“Mais, no. Mignon, she want da fancy white chasse-femme, not da old lady traiteur, not my brudder, not me, her own man, not my mama who tell her what to do too much, she say. ‘If you love me, Ursin, you go fetch Miz Roz,’ she say. The roads, dey is all bourbeux. What she t’ink, I can jus’ fly here, me? Drive my boat down Main Street, huh? Come, come!”

Roz tied her shoes and pinned her veil in place. She considered the gun for a moment and finally strapped the purple satin holster to her thigh, sliding the pistol into place. She slung her midwife’s big white bag over her shoulder and scurried out the door to follow the massive Ursin to his mud-coated truck.

They sped along the paved road, scattering flocks of egrets and passing mule-drawn wagons poking along the highway. Ursin spun the wheel at a fork in the road and turned off on to a dirt and shell lane running between two water-filled ditches lined with chinaberries, tallow trees, and scrubby yaupon bushes. Beyond the tree line, cane fields spread out flat and flooded. The truck ran over a cottonmouth snake four foot long in the roadway and buried it with the mud splashed from its wheels as Ursin urged the old vehicle forward.

Roz hung on to the door handle as they bucketed along. “Where are we going?”

“We got a place out by Catahoula. The water, she high, no?”

“Yes, I hear the Mississippi is near flood level with all the rain and the snow melt from up North. I worry about my family in New Orleans, and I guess they worry about me.”

“Da Teche ridge, she don’t flood, even if da levee go. T’ings get too bad, we go by my papa’s place outside Chapelle.”

“How many children do you have?”

“Sept. Seven livin’. Mignon and me, we been married since we was seventeen, you know. You take good care of my old lady, huh? She tetu, likes her own way, but I don’t want to lose her, no.”

“I’ll do my very best.”

“C’est bon.”

They came to a small settlement where most of the homes were raised on cypress piles and connected to enormous, barrel-like fresh water cisterns. A small rain-swollen bayou fronted the houses and beyond that, the great, grassy wall of the levee held in the waters of the Atchafalaya swamp. Ursin stopped the truck in front of one of the more substantial cabins, and two brindled black and white dogs with eerie blue eyes raced from the porch to greet him with muddy paws. He shouted them down, and without asking, scooped up the midwife all in white and carried her through the mud to his front steps.

“Your family does this very well, Ursin.”

“But of course,” he said so charmingly that Roz was convinced he had once been as slim and handsome as Pierre, despite his big belly and missing front tooth.

Inside the house, Mignon shouted, “Don’t you let dem dogs in here, Ursin. Aaaa-eee, dis baby comin’ fast, fast.”

Roz rushed into the front room where a cauldron of hot water bubbled on the wood stove. The room was swept clean and dusted. A long table made from a single, untrimmed cypress plank three feet across filled much of the space, its benches neatly aligned. Rag rugs and rockers sat not too far from the stove. Crockery and pans gleamed on wall shelves beside a sink that emptied out under the house. A picture of the Blessed Virgin hung nailed to the whitewashed bousillage wall made of mud and moss. Beneath the picture on a small table burned a votive candle in a ruby glass holder. Someone had gone out into the wet to gather a bouquet of yellowtop and daisy fleabane and placed the bouquet in an old green bottle beside the flickering candle. The house had floor space enough for babies to crawl and children to play indoors on rainy days.

“You have a very pleasant home, Ursin,” Roz said as she scrubbed up.

“Mignon, she been cleanin’ all day. Da kids, she sent over by her sister.”

“Y’all comin’, Madame Chasse-femme, ’cause dis baby, he ready to come out,” Mignon called. “Ai-yai-yai!”

Roz hastened to the large bedroom where Mignon lay on a double bed with a plump moss mattress covered in boiled, bleached, and mended old sheets. Ursin’s wife had fastened two rope handholds to the bars of the bedstead. She strained against them. Her belly heaved under the worn nightgown of flowered flannel. Her muscles bulged. She let out another cry.

“Dis one, he hurts more den all the rest.”

“Let me take a look. Don’t push. I see a foot.”

“Mais, no!”

“This isn’t your first. We have plenty of room to get him out, but I need to pull both legs down and make sure the cord isn’t in the way. This will hurt, but don’t push.”

The strength of the contractions squeezed the pelvic muscles against her hands. Roz waited for an interval and quickly drew one leg down, fought the muscles again, found a small foot and paired it with the other. She moved the baby down the birth canal.

Mignon swore, “‘Cre tonnerre!”

“Definitely a boy, a big-headed boy.”

“Ain’t dey all. We was gonna call him Toussaint, but now maybe he be Gros Tete, eh,” Mignon panted. She regarded the bloody, vernix-smeared baby with experienced and loving eyes. “He big all over.”

“A big, clean afterbirth, too. Can you rub your belly to help stop the bleeding? This being your eighth child, we need to help your womb to contract.”

“Tent’,” said Mignon doing as she had been asked.

“What?” Roz attended to the baby, wiping him clean while he fussed and squirmed, and dressing him in a diaper and shirt almost too tiny for the nine pound boy. Mignon had laid out the clothes and blankets in the nearby crib.

“Toussaint, he my tent’ child. Diphterie took my first born, and La grippe got one of my baby girls.”

Roz snuggled the newborn next to his mama and arranged the rags that would catch the clots and the abundant lochia following the birth of such a big child. She rolled the large woman from side to side, changing the sheets, even the sweat-soaked pillowcase. At Mignon’s direction, she found a clean nightgown in the big armoire and helped the woman put it on.

When everything and everybody was tidy, Roz went to look for Ursin. He wasn’t far off. Ursin sat on the front steps, a dog on either side of him, a hand-rolled cigarette dangling from his lips, and a bouquet of wildflowers pulled up by their muddy roots in his hands.

“You done in dere? I heard da baby cry.”

“Yes, you can go in and see your new son. He’s big and healthy. Would you like me to put those flowers in a vase?”

“Yeah, sure. Women, dey like flowers. I give the Virgin some, too, for my woman’s safety, you know.”

“I know.” Roz took the flowers and cut off the roots while Ursin went in for his visit. She found a jar to arrange them in and took the bouquet to Mignon, setting it on the table by her bedside.

Ursin held his son, but he stood, kissed his wife’s forehead, and settled the baby back in her arms. “Best I go get da kids. My belle-soeur, she lives down da Bayou Bouef levee road, got five of her own and one more due any time now. She probably crazy by now wit’ twelve runnin’ around.”

Ursin shook a finger at his wife. “My mama, she gonna be en colere, you don’t call her to come.”

“Go get da kids.” Mignon waved him away.

“I’ll sit with you until he returns.”

“Ye

ah, dis been good. No noise, all nice and quiet. No MawMaw Alida sayin’ da water not hot enough, da house not clean enough. Havin’ you take care of me and Toussaint, c’est bon. I gonna tell my sister, Cherie. She make her man come get you, end of May when she due. Don’t care if MawMaw Alida don’t like it. Ain’t no one good enough for her boys. She want Pierre to marry some nice country girl. I say, he been to da city, won’t no’ting but a city girl do now.” She looked pointedly at Roz.

“That can’t be. I’m married and in the midst of a divorce. Afterwards, I won’t be welcome in the Church, and I refuse to buy an annulment. In fact, I’m thinking of joining the Methodist church permanently.”

Mignon shrugged. “Won’t dat jus’ burn MawMaw Alida’s tailfedders, huh? Pierre don’t care about religion. Help me up. I got to get dinner on da stove.”

“Oh, no. Let me do that for you.” Roz spoke without thinking.

“You cook?”

“Ah, I can boil water.”

“Bon. Put some rice in it. You stay to eat. Me, I give Toussaint da tit.”

****

By the time Ursin returned with a truckbed load of children, a pot of gumbo and a pan of cornbread sent by Cherie, the smell of scorched rice filled the house.

“T’aught da place was burnin’ down, me,” he grumbled, but he settled the children around the table even though they clamored to see the new baby.

“Hush, hush, he sleepin’. You get to hold him after supper.”

Mignon, who insisted on getting up, dished rice from the center of the pot into bowls and ladled the still warm crawfish gumbo over it. She let Roz cut the cornbread into squares and pass the pan around the table. The children scooted over to let the midwife sit. A pitcher of cold milk from the icebox by the sink sat at the ready to be poured into tin cups, and the coffee pot was prepared for after the meal. Spoons remained down until they said grace with Ursin thanking Le Bon Dieu for the safe delivery of his wife, his fine new son, and his seven other blessings. “And Lord,” he added, “Let da rains stop and da levee hold. Amen.”

After the meal while the older children took turns holding the baby and the toddler crawled into his mother’s lap looking for attention, Ursin set two pierced cans of sweeten condensed milk in hot water to make a treat for the family. While the milk caramelized, he drew Roz aside.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

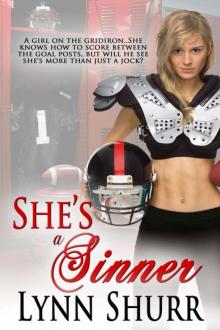

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner