- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Sister of a Sinner Page 23

Sister of a Sinner Read online

Page 23

He showed her his mayhaw grove where he kept bee hives to produce honey and knocked the ripe red fruit into his boat in late spring for Rosemarie’s jelly making. “You can close a wound and keep it clean wit’ honey. Spider webs are good for stopping blood,” Nestor said as they passed beneath a giant, communal web of large banana spiders.

Xochi nodded. “Have you always lived like this? Do many patients come out here to see you?”

Whap! Nestor brained a nutria only half dead and chucked it into the bottom of the boat to keep company with the others and a pail of catfish he’d caught along the way. “No, I come to live here after my wife passed. Me, I’m done wit’ haircuts and shaving, and young priests who got no respect for what I do. Mostly, I gather herbs for Rosemarie and let her handle the town folks. Seven kids, four daughters, and not one interested in receiving my gift. The best of the lot went to be a nurse. I’m eighty-two and need to do this now.”

Xochi absorbed as much about living off the swamp as she did about healing. In the evening, she made cornbread from a mix while Nestor skinned the catfish and removed the mud vein that tainted the flesh of wild caught fish. He fried them whole, heads off, and dressed up a can of green beans with bacon and a dash cayenne for a side. Dessert? Usually canned peaches in heavy syrup or jars of syrupy figs grateful clients left on his doorstep and always, sweet tea and black, black coffee.

When Xochi made a run into town, she supplemented their diet with fresh fruit, filling a tupelo bowl Nestor had carved with grapes, peaches, oranges, plums, and bananas. Sometimes, she picked up a pint of vanilla ice cream, about all the tiny freezer had space for besides ice trays, and made sundaes with the fig syrup. Nestor enjoyed that. He seemed very hale for his age and the radiated the jolly pink aura of a man happy with his life. Still, she saw patches of that khaki color denoting disease, perhaps only the ills of a very old man, but hard to tell when he denied any infirmities.

Most of the week, Tall Pines Lane lay deserted, but come the weekend, the cabins that lined the road filled with families getting out of town to their camps for fishing and crabbing or simply lazing in a hammock strung between two trees. Miles and miles of bad road away from a pharmacy or a hospital, Nestor’s business picked up on Saturday and Sunday.

Xochi witnessed him revive a boy who had played too hard in the hot sun and collapsed by lying the child down on his bed, placing the kid’s hands into cold water, and praying mighty hard. He asked her to join in, and she did, stroking the hot, dry forehead, lending strength. In a short time, the child opened his eyes, ready to play again, but Nestor advised a nice, cold pop in the shade might be a better idea. Later, he found a fifth of whiskey on his doorstep.

He often complained about loud music disturbing his peace and four-wheelers churning up the dust, but he never turned away a person who came to seek his help. A distraught young mother with a howling baby on her hip made her way to his door. “My husband says if I can’t shut him up, we’ll have to go home where he can watch his Braves game in another room. Jordy is teething, and nothing seems to help.”

Xochi watched as Nestor took a shiny dime from a roll on his work counter, a piece of rough split cypress with four legs pounded into it. Using a small auger, he drilled a hole in the coin, ran a safety pin through it, and pinned it to the baby’s slobber-wet shirt. The bemused infant stopped whining and focused on the new object within his range. He made a few grabs for it. Xochi cupped the baby’s chubby cheeks and kissed the top of his sweat-soaked head. Jordy offered her a smile with the tiny chips of new teeth shining through his pink gums.

“Oh, thank you!” his mother said to both of them.

Nestor held up a hand. “No t’anks, never. I share my gift. Now if he start up again, give him a half teaspoon of dis lizard tail tea.”

Xochi envisioned Nestor collecting the snapped tails of the green anole lizards that walked up his walls and sunned on the tree stumps. Why not eye of newt, too? Her skeptical expression gave her away.

“Not dat kind of lizard tail, da plant we find in da swamp. I show you next time we go out.”

A person with a bad cough showed up on the porch. “I’m scaring off the fish,” he claimed.

Nestor took the red seeds of the mamou plant—also known as coral bean—that grew along his fence, its scarlet flowers long turned to black pods splitting open with a free home remedy. He boiled a few in a half cup of water, drained the tea into a mason jar, and added a dollop of his honey, lemon juice, and a good slug of whiskey from the gift bottle. “Dat should do you. Keep it cold.”

The fellow, a regular customer, offered no thanks, but brought by a string of bass he caught later. A batch of dense chocolate brownies on a paper plate covered with a napkin to keep the flies off appeared on the porch swing. They ate well on Saturday night. Nestor topped off his coffee with a shot of the whiskey, but Xo declined.

Xochi learned to concoct mamou cough syrup and other remedies: elderberry buds for headache, fever, chills, and eye washes, the weird brown fruits of the pawpaw tree for constipation. All interesting and possibly effective, but what worked best for her was the laying on of hands as she prayed. She doubted she would ever tell anyone about the warmth that flowed from her body and into another person to comfort them, and certainly would never claim to be able to heal, but as Nestor said, word got around. He thought she could most likely heal from a distance with her prayers as long as no water came between her and the patient. “Stay on dis side of da bayou,” he directed, not joking at all.

Learning as much as she could as fast as she could, still, Xochi lived for Sundays, her day off. She offered Nestor a ride to church, but he declined. “A man old as me ain’t got much left to confess. Besides, I have my own ride. Dat old truck don’t look like much, but I worked as a mechanic for Aldus Thibodeaux at his gas station years and years. Her engine, she is good if I want to go to town.”

A little relieved that she wouldn’t have to transport Nestor back and forth, cutting into her time spent with Junior, she went off to meet him and the Catholic branch of the Billodeaux family for early Mass. She held hands with Junior under the cover of a prayer book, but Mawmaw Nadine looked at them with knowing eyes whose white brows rose if both of them didn’t get up to take communion.

Beignets and coffee at Pommier’s Bakery followed, then Sunday dinner of pork roast and gravy or prime beef with the Episcopalians of the clan later. Under the pretext of taking in a matinee at the theater in Broussard, conveniently located near a couple of chain hotels, they got a room for some afternoon delight. If the movie showed again at four, they actually went, filling up on nachos and hot dogs for dinner and getting Xochi back to Nestor’s before the alligator brigade took up residence in the yard. When she went for groceries on Monday, she stopped by Ste. Jeanne de Arc for confession. Obviously, Junior didn’t always do the same.

July raced toward August training camp for him, this year held in the kinder summer climate of West Virginia at a luxury resort, too far away for visits home. After that, preseason games started where Junior had to prove himself, Tom and Alix kicked, and Dean played a quarter or two before turning it over to his backups. During the regular season when Junior would be working out in New Orleans, on the road, playing Sundays, he wasn’t likely to get the time to drive the six-hour round trip to Chapelle. How she would miss him, this man of many talents she’d tried to push away simply for being a few years younger than herself. His absence would be unbearable.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

The rusty chains of the porch swing creaked as Junior and Xochi spent their last afternoon together before he caught a redeye flight to West Virginia, reporting on Monday for the grueling two-a-day exercises. The weekend campers loaded their pickups and SUVs and headed out. A motorboat still on the water purred by, and the flock of snowy egrets with a rookery in the area circled in the air before roosting for the night.

They rocked slowly back and forth with the slight breeze keeping off the mosquitoes. After executi

ng their movie ploy, they returned to the cabin to have a dinner of nutra rat spaghetti with the meatballs finely ground and covered in tomato sauce sopped up by French bread soaked in garlic butter. Xochi joked a good thing they’d both had the same meal as she shared a few kisses with Junior before nestling against his great chest, trying to live in the moment and forget he would be gone for a long time after Nestor called the gators.

Beneath her ear, his heart ticked up a few beats as Junior shifted on the swing. “Everything all right? If you need the bathroom after that meal, I can swear snakes don’t come up through the toilet.” She tried to keep things light, but what if he thought they should break up or cool it for the season in order to take advantage of the freedom she’d once stupidly offered him. But no, his aura still shone with the deep violet of his love.

“Good to know about the absence of snakes in the john, but I have to stand up for a minute and get something out of my pocket.” He withdrew a ring box, not from LeClerc’s in town, and sat down beside her again. “I want to give this to you before I leave. I know you might not be as ready to commit as I am since I’ve been ready for years, but I’d like you to wear this as sort of a promise ring.”

He flipped open the box with one of his big thumbs. An amethyst of deepest purple nested in a unique setting glowing against white satin. Golden blossoms surrounded the stone, each with a center of a tiny white diamond. “A jeweler in Lafayette makes rings to order. An amethyst is supposed to help with healing, bring good dreams, and protect from evil, or so he told me—since I won’t be around for a while.”

“So, it can’t be an engagement ring?” she asked, looking deeply into the most sincere brown eyes a man could possess.

How he brightened. “It could! Unless you want a diamond, which I would totally get for you.”

“No, this is thoughtful, wonderful, and unique—very much like you, Junior. Put it on my finger, and I will promise to marry you.”

His smile was broad, and she loved that little gap in his front teeth all over again and the way his huge hand trembled a little when he slipped it on. In the background, Nestor called the alligators with grunts and sooeys and here, gator, gator, gator. Junior frowned. “This isn’t the way it’s supposed to be. We should have had a candlelight dinner and soft music playing in the background, not nutria spaghetti and hog calls.”

“You said something like that to me in Cozumel, but it makes no difference to me. We are officially engaged. Proving we think alike, I have something for you, too.” Xochi reached into the pocket of her gaily flowered Sunday dress and held out a chain. A shard of amethyst dangled from the end of it. “Also good for staving off drunkenness and keeping a man faithful.” She hung it around his neck.

“I don’t have a problem with either, but I’ll wear it always. Te amo, Xochi.”

“Te amo, Junior.”

As they leaned in for a kiss, a sharp ping sounded near Junior’s head. The rusty chain severed and dumped them onto the porch. From underneath his body, Xochi said, “I should have known that old swing wouldn’t hold both our weight.”

Junior knew better. The sounds of the fight in Cozumel came back to him. With Diaz still on the loose, he moved to put his body between the shooter and Xochi. If he died doing so, at least she had accepted his ring and made him the happiest man alive however briefly.

“Not the swing, Xo. A bullet. Belly toward the door beside me. Let me cover this side.”

They began a desperate crawl across the aged cypress deck. Another slug sent splinters of gray wood into the air. The door flew open almost in their faces.

His hands still covered in nutria blood from the feeding, Nestor stood there with a double-barreled shotgun, the one he took along in his boat and propped in a corner each night. “Stay away from my gators, you!” he shouted into the on-coming dusk. Their forms louche and dark, a few of his pets slithered into the yard. “You t’ink dey easy pickings? Take dis!” He let loose with a blast.

Junior urged Xo inside the cabin. Nestor took a step forward to let him pass and emptied the other chamber in the general direction of the next shot, which lodged in the doorframe. Junior pulled the old man inside and slammed the door. “He isn’t after your gators, Nestor.”

“How you know? Won’t be da first time someone t’ink they can take a gator wit’out getting a tag or going into da swamp.” Beneath the house, some of those gators disturbed by the ruckus splashed into the water.

“Because he aimed at us. Xo, call 9-1-1.”

She made her way carefully to a black wall phone Nestor must have brought from his last home. “Shots fired on Tall Pines Road, Nestor Leleux’s house, the last on the lane. Please hurry!” She blurted out her name and the telephone number. Another pane of glass shattered.

“Now, I’m mad. Glass costs good money, no?” Nestor said. He chambered two more shells from a carton on the spool table.

“You got any other weapons I could use?” Junior asked.

“Deer rifle in my bedroom closet and some sharp, sharp skinning knives on da work table.”

Before Junior could find the rifle, running footsteps sounded hollowly on the boardwalk as the gloom of night deepened. He grabbed a knife. Their attacker kicked in a door that had never known a lock. Dressed in black, his boots muddy from traversing the edge of the swamp, Diaz stood before them. He gripped an assault rifle and fanned its muzzle across the three of them without pulling the trigger. Holding the knife down and close to his side, Junior moved in front of Xochi

“Viejo, put down the gun. No need for you to die. I come for the girl to complete my father’s last wish, that she have her heart cut out, and the big one stands in my way.”

“Don’t listen to him, Nestor. He is the son of the devil and will kill you in the end,” she said.

Unconcerned, Diaz shrugged. “Take your chances.”

Nestor did. He pulled the trigger of the shotgun, but this time his knees buckled with its kick, and he drooped to the floor, his aim skewing upward toward the ceiling. A few bits of buckshot bounced off the assailant’s armored chest as he twisted away. A couple scored his cheek., sending rivulets of blood down his face. The rest dug into the rafters and sent fragments of herbs raining down like autumn leaves.

Junior took advantage of the distraction and did what he did best, went in low for the tackle, thrusting forward so powerfully he knocked Diaz out the doorway, across the porch, through the flimsy railing, and down into the alligator pit. He lay there on top of the flailing Diaz, slightly stunned by hitting his head on the edge of the porch.

Not all the gators had abandoned Nestor’s yard. Big Ben snapped at an arm coming within his range, not Junior’s. Like all the kids at the ranch, he’d been schooled not to wave a limb around gators who were mostly attracted to motion. That zigzag running, no good. Just run fast as you can. He shook his head, trying to clear it, as the distracted gator jerked Diaz’s arm hard enough to dislodge him from beneath Junior. The man attempted to discharge his weapon into Big Ben, but the gator already had him in a roll. The bullets clattered into Nestor’s makeshift fence. Unconcerned, the giant gator worked on ripping that arm from the socket. It succeeded with a fierce shaking of its clenched jaws and a crunching noise as the bone and sinew severed.

Diaz screamed, making Junior’s ears ring, but the man did not surrender. He ran for the gate, leaving as the gator tilted his head and wolfed down the arm. Instinctively, Junior pushed up to pursue him—and drew the attention of Big Ben ready for another snack. Chomp into the meat of his bicep. The only thing to do when a gator got your arm was to hold tight and roll with it while trying to get at its eyes. They tumbled around, once, twice, three times, the gator unable to get a better grip as Junior hugged the scaly belly of the beast against his chest.

He caught a flash of color on the porch. Xochi fired the shotgun, but the pellets bounced off the reptile’s horny plated back. More annoyed than hurt, Big Ben loosened his grip. Junior broke free and drove the knife clutched

in his other hand into one murderous yellow eye. The gator backed off, made an amazingly agile turn with a flick of his mighty tail, and retreated under the house. They heard the splash of his huge thousand-pound body entering the water, then momentary silence after the chaos.

Gradually, the cricket frogs began to chirp. Far off, sirens sounded. Junior pressed himself over the edge of the porch to find Xochi gone. Inside the cabin, he discovered her kneeling by Nestor and performing CPR, her hands pressing over his heart, her lips giving the old man breath. The smile of his dentures lay beside him on the floor. Of course, she knew CPR. Anyone who’d served as a Camp Love Letter lifeguard knew the drill.

She looked up at Junior. “Heart attack, I think.”

“I’ll take a turn when you get tired.”

“You’re bleeding again.”

Junior regarded his arm. “A little bit. Didn’t even feel it with the adrenaline rush.”

“You will. Press a towel around your wounds and sit down for heaven’s sake.”

The cacophony of emergency vehicles entered the lane. A familiar voice shouted, “Police! We’re coming in.” Tony Ancona appeared in the doorway going low while Officer Chauvin went high. Both wore the same uniform.

“Tony? Diaz is gone. He ran into the woods minus an arm thanks to Nestor’s yard dog who got a taste of me, too.” Junior lifted a blood-soaked towel from his arm.

“But Nestor needs an ambulance.” Xochi continued to pump the old man’s heart. Her patient opened his eyes a tad, turned his head, and vomited nutra rat spaghetti out the side of his mouth. “Oh, good,” she said.

“Yeah. We have an ambulance with us out at the end of the road and a fire engine. You never know in these situations. Chauvin, you want to track the perp or stay here?”

Officer Chauvin eyed the stinking puddle on the floor and opted to search for Diaz with the night growing deeper. He took the flashlight off his utility belt but kept his gun handy. “We might have to call in the dogs.”

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

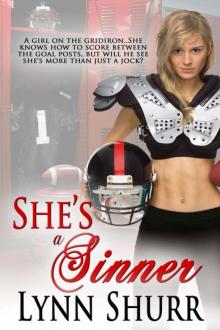

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner