- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Page 18

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Read online

Page 18

“Are you lost? The clinic is in the front of the building,” the nurse with the stern voice said. She dazzled in pure white from the tips of her shoes to the large, starched cap covering most of her short, dark hair shot through with a little gray.

“I’m looking for the midwives’ class Dr. Landry said started today. I’d like to register.”

The dark women chuckled. Some outright threw back their heads and laughed. They dressed in long white skirts and sturdy shoes, loose blouses, and spotless aprons. All of them had heads wrapped in tignons, covered with makeshift veils of muslin, or capped with sunbonnets. Here and there, a gold tooth glittered as they smiled.

“Order!” The nurse in charge clapped her hands. The laughter subsided. “You were misinformed. This is a class for experienced Negro midwives. Our goal is to improve and certify their skills and lower infant and childbirth mortality in the parish. Isn’t that correct, ladies?”

“Yas’m,” a few of the students murmured without enthusiasm.

“For poor colored women living in rural areas, the midwife may provide the only pre-and postnatal care she will receive, whether it is due to lack of money or the reluctance to be examined by a white doctor.”

“Uh-huh,” several members of the class agreed as if they responded to the gospel at the Baptist church.

Roz stood her ground. “I see. Well, there must be poor, rural white women in the same situation. I’d like to learn to attend to them.”

“Doan look like she even married, let alone birthed a baby herself,” said one of the students who was as black as a stovepipe and as broad as an oven.

“I am married, and I miscarried my first child. I think it would be a fine thing to prevent that from happening to other women.”

A few in the group murmured sympathetically, but the blackest of the women spoke up again. “Dis class ain’t for yo’ kind, little white lady.”

“I decide who attends, Mrs. Senegal. You may sit in, Mrs…” Nurse Emory gathered her authority about her and stared down her class with a steely gray glance.

“Mrs. Boylan, Rosamond Boylan. Roz would be fine.”

“In this class, we will address each other by our proper surnames. If you should succeed in completing the course,” Nurse Emory paused as if that possibility were doubtful, “you will be known as Midwife Boylan. Ladies, please make room on one of the benches for Mrs. Boylan.”

None of the dozen students moved. Nurse Emory stared at the first row, and a general shifting of wide-hipped women occurred. Roz perched on the end of the bench, and broad Mrs. Senegal bumped the midwife next to herself harder to put even more space between her and the white lady. Roz opened her purse and took out a leather-bound notebook and a small pencil. The members of the group snickered.

“Order!” shouted Nurse Emory, who got what she wanted. “We will begin with cleanliness and the proper washing of hands for the prevention of infection. Orderly, fill the basins!”

A colored man, who had been standing by in an adjoining room, entered with a steaming kettle and filled three basins set on the long table. Nurse Emory beckoned to the back row. “They who are last shall be first.”

The midwives immersed their brawny arms in the steaming water to the elbows and scrubbed with antiseptic soap. Nurse Emory monitored their technique and checked their nails. Roz came last in line. She removed her gloves, dipped her hands, then pulled them back.

“Do you have a problem with using the same water as a colored woman, Mrs. Boylan?”

“Oh, no! It’s just that the water is still very hot.”

“As it should be. In to the elbows. Scrub under the nails.”

Roz did as she was told though her arms turned red, her fingers wrinkled, and her manicure deteriorated. She held out her hands for inspection, as had the others.

“Those long nails will have to go, Mrs. Boylan. They harbor germs and are difficult to keep clean, not to mention the danger of punctures. Get rid of the red polish as well. If you come back tomorrow, you will have your head appropriately veiled. This is not a Sunday church service. Also, you will need an apron and practical shoes.” Nurse Emory stared at Roz’s patent leather pumps.

Roz took her seat among the women who did their own laundry, scrubbed their own floors, and worked their own gardens. Their competent hands with thick, clipped, and yellowed nails hadn’t hesitated a second to plunge into the steaming water. Once again, she was in over her head, but by damn, she would be here tomorrow!

****

Roz searched through her trunk for a suitable dress and found one of gray so out of style its hem still reached mid-calf. She snipped off the broad lace collar and cuffs. Then, taking a deep breath, she cut her long nails one by one. This action caused her more pangs than mutilating the dress. Lace in hand, she went to find Widow Perdue.

The widow was finishing up dinner on a boarding house-sized range. Roz could tell the boarders would be eating rice and gravy again tonight, cabbage boiled with salt meat, a platter of thinly sliced ham, and bread and butter. There was a tarte a la bouie for dessert. Since the widow never lacked for milk and eggs, she specialized in custards and puddings.

“Excuse me, Mrs. Perdue, but I wondered if I might trade this lace for one of your white aprons and perhaps, a pillowcase.”

“Whatever for?” the widow said as she dished the cabbage into a bowl with a slotted spoon.

“I’m training to be a midwife and need an apron and a veil. My funds are rather short at the moment, and I thought—”

“I have no need for lace, none at all, being widowed these thirty years, but I do understand why a woman might have to make her way in the world alone. You’re welcome to take one of the mended aprons and an old pillowcase, too. I approve of women learning a trade. Wish I knew more than cooking and cleaning, yes, I do.”

“Thank you. Could I help take the dishes to the table?”

“Why, that would be very helpful. You’re not as bad as they say, after all.”

As Roz backed through the kitchen door with the platter of ham, she caught sight of a pair of pictures on the whatnot shelf. “Your grandchildren, Mrs. Purdue?”

She nodded with her head over the paper-thin slices of meat. “My son as a toddler and my new grandbaby,” the landlady answered with pride.

“I think you could make something very nice with the lace for your grandchild in exchange for a discount on next month’s rent.”

“It’s a deal, then. Be a dear and go back for the bread and gravy.”

The schoolteachers, already seated, raised their eyebrows and whispered to Roz as she set down the breadbasket and took her seat next to them. “Wowie, from being a bad woman to a dear in only one week. I need to know your secret, Roz. My principal suspects I smoke, and he cautioned me about setting a poor example for the children, yesterday. I told her she smelled the aroma from the drummer’s cigars,” Edna commented.

Faye looked at Roz’s hands as she passed the gravy boat. “Have you been doing your own laundry, city gal? You know the washerwoman comes by on Thursday and doesn’t charge much, though I wouldn’t give her any silk undies.”

Roz viewed her ravaged hands. “A hazard of becoming a midwife, I guess, but we were informed this is a suitable career for married women, even women with children. That’s a good thing since everyone in the class is married already.”

Edna sighed. “If we marry, our contracts aren’t renewed. Not that we’re likely to meet anyone in Chapelle, and if we go out to the Barn to have a little fun, Principal Gates is sure to hear about it.”

“The whole town will know the very next day,” Roz guaranteed.

Bernard Toomey, the chemistry teacher, sat across from the women. He had lived with his mother until her death when the rest of the family sold the house out from under him. He twisted the ends of his small, waxed moustache and adjusted his tweed coat and bow tie. “Ahem, as teachers we must set a moral standard in the community. Please pass the rice.”

“Oh, go f

ly a kite, Bernie!” Edna told him.

“I’m free tonight if you ladies want to go dancing,” offered a traveling salesman in a checkered suit. He stayed in one of the attic rooms when he passed through town.

“Sorry, papers to grade, but we could have a smoke in the parlor after dinner and check out your wares.” Faye vamped with a flutter of eyelashes.

“Finest hair care products in the U.S. of A, Miss Faye,” the salesman claimed.

“See you after dinner, then, big boy,” Edna answered with just a hint of Mae West in her voice.

Bernard Toomey took a large swallow of his glass of milk, dabbed his moustache, and refused to talk to anyone except the landlady for the rest of the meal.

****

Feeling incredibly self-conscious with a pillowcase folded and knotted behind her head, Roz took her seat on the end of the bench at the next day’s class. Nurse Emory entered from the small kitchen where meals were prepared for patients and coffee was always on for the doctor and nurses. A whiff of dark-roasted brew made Roz salivate. She had wasted a great deal of time trying to make the pillowcase veil attractive, and failing in that, simply getting it to stay on her head. Breakfast had been a heel of a stale loaf filled with cane syrup and washed down with water. At least, she remembered to bring a lunch in a paper sack today.

“Still with us then, Mrs. Boylan? Let me see your hands. Better, much better. Head covered, more practical garments. Good. You will be sorry if you continue to wear high-heeled shoes, however,” Nurse Emory warned.

“Yes, ma’am. I’ll be getting other footwear as soon as I can. Would tennis shoes do? I have a pair of those.”

“She gots shoes jus’ to play tennis wit’. Look like we be going to school wit’ Miss Helen Wills,” quipped one of the midwives sitting behind Roz. Beulah Senegal expelled a single deep laugh.

“Tennis shoes are quite acceptable,” Nurse Emory said in a quelling voice. The class came to order.

“Childbirth is a natural function of a woman’s body. It is your duty to interfere with that function as little as possible or great harm can occur. To gain a better understanding of parturition, that is childbirth, we will study today the anatomy of the genital organs and the changes that occur in the female body during pregnancy.”

With the snap of a wrist, Nurse Emory pulled down a wall chart showing the insides of a naked woman. Beside it, she tacked a smaller picture with a gynecologist’s view of the business end of a female. A few eyes widened. They’d seen what was on the smaller chart dozens of times, but actual insides remained a mystery.

“Pay attention, class. After the lunch break, we will have a short test on the terms. Repeat after me—ovaries.” The instructor stabbed the body part with her pointer.

Although Roz dutifully repeated with the rest of the class, this part went easy. The nuns had taught female anatomy as well as abstinence in hygiene class at the Academy. They had also checked for clean fingernails. She was beginning to feel right at home.

The lunch break came, and the midwives turned on their benches to form small groups as they opened their tin pails. Nurse Emory disappeared through the door to the food preparation area. Roz opened her paper sack and took out the three peanut butter and marshmallow fluff crackers she’d made that morning and a small, greenish orange Henri had brought her from his mother’s yard.

Beulah Senegal looked over toward where Roz sat alone. She bit into a fried chicken leg and watched Roz daintily eat her crackers. “I had me a two chicken delivery las’ night. Didn’t waste no time ringing dose necks and frying ’em up in a pan. What? You ain’t gonna run over to the St. Rochelle place an’ have a fine, hot lunch like you did yesterday, gal?”

“Yesterday, I ran to my boarding house and ate pretty much what I’m eating today. I no longer live with the St. Rochelles.”

“Dat so? Be a frozen day in Lou-siana ’fore I live on crackers and mashed nuts.”

“Oh, it’s supposed to be very nutritious. Did you know a colored man named Dr. George Washington Carver invented three-hundred uses for the peanut? He had great faith in them,” Roz replied brightly. Black, bulky Beulah Senegal scared her, but she wasn’t about to show it.

“Do tell. Here you be, pecking away at cracker crumbs like some little, yaller chick. I think you too puny to bring babies into the world, Peep.”

“And I think I’m tired of people telling me I’m too weak to be worthwhile. I can keep up with you, you’ll see.” Say it often enough and it might come true, Roz hoped.

“Ha!” Beulah turned back to her group of friends and left Roz to peel and eat the orange that tasted sour after a lunch of marshmallow fluff and peanut butter.

In short order, the midwives packed up the remnants of ham sandwiches, chicken bones, and the casings of cold boudin sausages. The only student who had a more humble lunch than Roz was a nearly toothless granny who had gummed down cornbread and syrup. The women filed out across the soggy lawn toward the outhouses near the bank of the bayou.

The little granny paused by Roz and said kindly, “I ’spects you can use da white people’s toilet up on second flo’, honey. Cut through da kitchen and it take you out in da hall.”

“Won’t Nurse Emory be angry if I do that?”

“Oh, she ain’t so tough. I was da one brought her into dis world out on the Island more’n thirty years ago. She like her grandmama, wantin’ to do good.”

“Thank you, Mrs.?”

“Miz Savage, but you call me Granny Sue like all da rest.” The smallest and oldest of the midwives tottered after her associates across the back lawn to the colored facilities.

Roz walked into the kitchen area, startling two workers who were doing up dishes and wiping down trays. A table where the staff could sit and relax stood empty. Roz scooted out into the hall. Through the glass doors at the front of the clinic, she observed Nurse Emory leaning against one of the porch pillars and drawing on a cigarette. Not waiting to get caught, Roz darted up the stairs and into the clearly marked ladies room.

After relieving herself, she checked her appearance in the mirror over the sink. Fluffy blonde curls escaped around the edge of the makeshift veil. No wonder Beulah Senegal called her Peep. She pushed them back only to have them spring out again. Finally, she pulled the pillowcase low over her forehead. She hadn’t bothered with makeup or hair cream and did look pale and puny, she decided, but no help for it. Oh, the time! She checked her wristwatch and bolted from the room.

Pierre Landry caught her by the elbows just before she smashed into him. “Running upsets the patients, nurse,” he said with a wry smile. “They think someone is dying when you rush.” He took a closer look. “Is that you under there, Roz?”

Roz looked up knowing she turned red. She hid her chapped, stubby-nailed hands behind her back, remembering all too well the feel of his lips, the brush of his moustache against her cheek. “Yes, it’s me. I’m attending the midwives’ class—which you neglected to tell me was for colored women.”

“Sorry, I didn’t know. Nurse Emory asked me to speak to the class toward the end of March about the complications of pregnancy and childbirth. She didn’t mention any restrictions on who could attend. Still, she allowed you into the class. Is it going well for you?”

“Easy so far.”

Below the couple at the base of the staircase, Nurse Emory called out, “Mrs. Boylan, back to class. Don’t take up Dr. Landry’s valuable time.”

Roz fled down the stairs without saying good-bye. Nurse Emory followed behind her, back to the classroom. The tests were handed out, and when it became clear that some of the women could neither read nor write, she asked those students to form a line for oral quizzing. Roz finished well before the rest of the class and took her paper up to the teacher.

“One hundred percent, Mrs. Boylan. Very good. Take your seat.”

That left plenty of time for Roz to speculate that Nurse Emory was probably a better match for Pierre than she, even if the woman had passed thirty a while

ago. When a pounding began on the outer door, the nurse gave her the nod to answer it.

A young colored man, barefoot and wearing only denim overalls, asked in a panic, “Miz Senegal in dere? I needs a midwife. Baby’s comin’! My mules and wagon’s out front.”

“Dat you, Roscoe?” Beulah Senegal heaved to her feet. “You come out wit’ no shoes nor hat, boy, Maisie’s gonna be a widder to pneumonia ’fore dis baby comes. She a first-timer,” Beulah explained to the class in general.

“Primipara. Repeat,” ordered Nurse Emory.

The class followed her lead, all except Beulah who headed for the door. Roz shot to her feet. “May I go with you, please? I’ve never seen a birth. I’ll do whatever you need me to do.”

“Most likely what I needs you to do is stay out my way.”

“I think it would be beneficial for Mrs. Boylan to see the birth, Midwife Senegal. She might want to change her mind about midwifery as a career if she hasn’t the stomach for it,” Nurse Emory suggested, though it seemed more like an order.

“Oh, sho’. Come on wit’ Roscoe and me, Peep. See if you gots what it takes. Roscoe, we needs to stop by my house and pick up my bag.”

“But Maisie…”

“She still on her feet, Roscoe? Her water broke yet?”

“Yas’m, and no’m.”

“We in no hurry, den. Be hours yet by my guess.” Beulah lumbered out the door followed by Roz and Roscoe.

After Roscoe pushed Beulah Senegal on to the front seat of his farm wagon where she took up most of the space, the young man scratched his close-cropped head. “Doan know rightly where to put you, Miss.”

“I’ll ride in the back.”

“I can put down some sacks for y’all to sit on.”

“That would be fine, Roscoe.”

“We in a hurry or not, boy!” Beulah grumbled, but the first-time father spread the sacks and helped Roz up into the wagon bed.

As they headed to the edge of town where the Negroes had their shanties, heads turned in their direction. One of those heads belonged to Verna Harkrider. Roz gave her a merry wave. She wondered if the vicious gossip recognized her and how Verna would translate the wagon ride into something scandalous.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

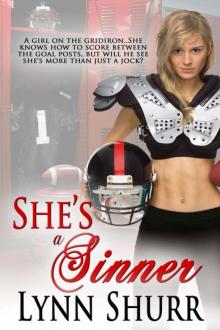

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner