- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Page 12

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Read online

Page 12

Roz put her arm around her baby sister. “Don’t cry, Roxie. I’ll call. I’ll write. In the summer, you can visit me.”

Roxie shoved her sister’s arm away. “I’m not crying for you. Mama says there will be a big scandal when the divorce papers are filed, and I must be protected from the gossip. They’re sending me to Mt. Carmel Academy all the way out in Rainbow right after Christmas when the nuns can take me. I’ll never see Artie again, and it’s all your fault!”

“Oh, Sis, Artie will still be living with and off of his parents when you graduate. By then, you’ll see he’s no great catch.”

“Oh, certainly not as great as Burke Boylan. I wish you’d killed him and gone to jail. Instead, they’re sending you straight to Dr. Landry because now you’re damaged goods, and no one else will marry you.”

“Who said that?”

“One of Mama’s friends. Mama was crying to her because you wanted a divorce. You always get everything you want. I might as well be dead myself!” Roxie bolted from the swing and ran to her room.

For the first time since shooting Burke, Roz began to tremble. She sobbed, but not for Buster. Being sent in disgrace to Chapelle, Louisiana, she doubted if she would be welcomed with open arms by her cousins or by Dr. Pierre Landry, a man who had held her, comforted her, and then left her without a word one month ago.

Chapter Eighteen

The journey to Chapelle passed slowly, some would have said tediously, as the vessel docked at each village along the way. The first night aboard, Roz slept poorly, but the farther from New Orleans they sailed, the more she was able to rest in the small, private cabin equipped with a moss-stuffed mattress on the bed frame and a mosquito bar over it. Insects weren’t a problem as the weather turned cool and rainy.

She watched the scenery pass from the windows of the tiny first-class lounge—the cypress trees tinged a rusty autumn orange, the wild pecans, basswoods and swamp maples bare, the live oaks and magnolias a glossy evergreen. In the larger second-class area, two Cajun families laughed and joked and chattered in their own patois. Listening and translating what she could with her private academy French, Roz gathered they had been to a wedding. Some of the comments were bawdy and made her smile to herself as she paged through a magazine or read a newspaper purchased at one of the stops. One of the men brought a squeezebox along and sang wailing Cajun songs to pass the time, or picked up the tune and encouraged the others to dance as he tapped a rhythm with his foot.

While she ate her solitary meals of plain but hearty food heavy on the biscuits and gravy, the Cajuns shared from baskets they brought aboard. They handed around a sack of oranges and a bunch of bananas purchased in the city to their children like candy. At stops, the men went ashore and returned with tinned sardines, crackers, cold boudin sausages, big dill pickles, and long French loaves if the town had a bakery.

As Roz walked the decks for exercise, black-eyed, dark-haired children raced past her playing tag and taunting each other in two languages. On the second to last day of her journey, as she sat outside wearing her gray Parisian coat against the damp and chill, one of the boys stopped their game and asked, “What kind of animal make dat fur?”

“Guess,” Roz told them, hungry for their company.

“Not beaver, not muskrat, not otter, nedder,” the oldest boy said, studying her collar with a trapper’s experienced eye.

The smallest girl shyly ran a finger over the lush, silvery pelt and guessed, “Bunny rabbit?”

“Stupide, Mimi,” her brother said. “Maybe wolf, no?”

“Fox, silver fox all the way from Russia,” she told them.

“C’est vrai?” the children exclaimed with amazement.

“Yes, it’s true. I bought the coat in Paris, France. Do you know where that is?”

The little girl shook her head, but the eldest boy shrugged. “You learn dat in da six grade. Next year, I don’t to go school no more, me. I trap and fish wit’ my papa.”

“Oh, but you should finish school!”

Roz received another Gallic shrug. “I can read, write, figure, speak da English. Dat’s all I need, Papa says. C’est finis.” The boy wiped out his American education with a wave of his hands.

“But you could grow up to be a doctor. Like Dr. Landry, do you know him? He lives in Chapelle.”

No, they shook their heads. They don’t live by Chapelle. At the next town, the families disembarked and piled into a wagon drawn by two mules named Clotilde and Alphonse and driven by Mimi’s parrain, as the little girl told Roz when she came to say good-bye. Roz pressed a shiny dime into her hand. “For a treat for you and your brothers and sister. Remember to share.”

She saw the father frown, his mouth half-hidden under a wide, bushy mustache, as Mimi displayed her gift. Though her own French roots in Louisiana were probably older than his Acadian origins, Roz knew he considered her a blonde, blue-eyed Americaine dressed in smart city clothes. She called out in her questionable French, “Un petit present pour mes amis,” and waved them an airy good-bye with her kid-gloved hand.

The father nodded curtly. “Merci,” he said. “Mimi?”

“Merci beaucoup, belle Dame,” Mimi replied, showing her manners.

Her papa lifted her into the wagon, and they started on their way home, mud from the wheels splattering up from the road. Whether her attempt to use French or her emphasis of the smallness of the gift convinced the man that she wasn’t offering charity, she would never know. Rosamond St. Rochelle was traveling deep into the country where Pierre Landry had been raised, and she never felt more out of place, not in Rome, Madrid, or Paris. Had he felt the same among the Creoles of New Orleans?

The boat whistle sounded, and the crew of Negro men who had carried a few crates ashore came aboard, pulled up the plank joining the paddlewheeler to the bank, and cast off the mooring ropes. That night, the only music came from their quarters among the cargo boxes, a lonely tune played on a harmonica and the moan of the blues. The next morning, the ship docked in Chapelle.

****

Roz wore her red hat for courage and her fine coat for style. She’d applied her makeup with care in order to make a good impression on Cousin André and his wife and whomever else she might meet that day. Above all, she didn’t want to appear beaten, bedraggled, or crazy the way Pierre Landry had last seen her.

Her hosts waited inside their auto by the dock, keeping themselves dry from the persistent drizzle that resurrected the ferns in the live oaks and dripped from the swags of gray Spanish moss festooning the trees. The bayou ran high and cloudy under the gangplank as Roz crossed. His gray felt hat pulled low over his eyes, Cousin André came running with an umbrella. He tipped a porter to bring her trunks along in a wooden handcart and hustled his guest to the automobile.

Cousin André, not really her cousin but her father’s, had a few years on Laurence. Both men stood tall and had a sort of portly presence that spoke of money and power, but Cousin André possessed a much larger bald spot in his fair, thinning hair and rarely went about without a hat to cover it. His wife, Loretta, short, plump, and olive-complected, allowed gray to streak in her thick, dark hair without resorting to dye as Emmaline did. Roz had to exercise her imagination to see them as a smitten Romeo and Juliet sort of couple who had married for love and settled far away from the disapproval of the St. Rochelles.

Loretta offered a hand across the seat as Roz slid into the back of the car. “Did you have a restful voyage, dear?”

“Yes, very restful.”

“With the last of my girls away at the Academy in Rainbow and the older ones married, we have plenty of room. Of course, our youngest is still at home, and eight-year-old boys like Henri can be a handful.”

“I’m sure Henri and I will get along fine, Cousin Loretta.” She knew well that the couple kept trying until they had a son, though Cousin André always spoke of his six lovely daughters with pride. Two of their female brood had studied at the Academy during Roz’s stay. Neither had been in her c

lass, however.

“Feel free to stay as long as it takes—as long as you want,” Loretta said delicately.

“I believe the standard waiting time for a divorce is one year, but I wouldn’t dream of imposing so long.”

There, that got the scandal out in the open and effectively killed the conversation as they traveled two blocks up from dock and four blocks to the right on Main Street to stop before a low, gracious home of white siding and deep green shutters. The house sat on a corner lot and was wrapped on two sides by a deep porch scattered with wicker furniture and draped by hanging baskets of Boston ferns that hadn’t yet been taken in for the winter. A boy peered through an opening in the railing and popped up to his full height when the grown-ups climbed the three steps to the porch.

“Ain’t she a looker, Daddy?” Cousin Henri said to his mother’s embarrassment.

André St. Rochelle cleared his throat in a way that made Roz miss her own father. “Henri, this is your Cousin Rosamond, and yes, she is certainly an attractive young lady, but it’s not your place to say so.”

“Hi, I’m Roz.” She held out her gloved hand, and Henri gave it a quick shake.

The boy had the dark eyes and hair of his mother, curly lashes that Roxie would have envied, and a sprinkling of cinnamon freckles across his nose. He possessed the assured smile and outgoing nature of a child who had rarely been reprimanded in any serious way.

“You’re supposed to have Janelle’s old room. She’s married away, so it’s free. It’s way down the hall from mine ’cause Mama says you need your privacy, but we can visit. I’ll show you where it is.” Henri raced to open the front door and sprint up the staircase.

Roz followed him to a comfortable bedroom at the end of the hall. It wasn’t far from the modern bathroom and offered a pleasant view of the backyard, which still had an outhouse with a sweet olive planted by the door in its far corner. The flowerbeds had been put to rest for the winter, but large azalea bushes screened the yard from the side street.

A double bed with a white iron headboard and an old-fashioned armoire took up most of the space, but a night table with a reading lamp had been squeezed in along with two ladder-backed chairs on either side of a window curtained in frills that matched the bedspread. Dainty posies patterned the wallpaper, a maiden’s room—how kind of them.

“Why don’t you have a rest until dinner? We’ll send up your trunks, and you can arrange things as you want them, but if you need help, call for the maid. Then, tomorrow we will all go to early Mass. It’s a pleasant walk if the rain lets up.”

“We used to make quite a procession when all the girls were home.” Cousin André gazed fondly at his wife. “Won’t it be nice to have a young woman with us again?”

Loretta didn’t respond to that question. “You’ll want to meet Father Grainger and some of our friends after Mass. Afterwards we treat ourselves to hot beignets at Pommier’s Bakery right on the square.”

“No, thank you. I’d prefer to sleep in.”

Loretta gave her husband an “oh my!” glance. “Yes, I can understand how the journey must have tired you. Perhaps, next Sunday.”

“No, I don’t think so. If I am going to be cut off from the sacraments as a divorced woman, I believe I should get used to doing without the Holy Catholic Church.”

Loretta was too shocked to reply, but Henri piped up, “Can I stay home, too?”

Cousin André came to the rescue. “No, you may not, son. Besides, you don’t want to miss out on those beignets, do you?”

“Guess not.”

“You may feel differently after you’ve been here a while. Most of the social life, such as there is, revolves around the Church, and you aren’t a divorced woman yet so—”

Loretta cut him off. “Let’s simply allow Cousin Roz to rest.”

“Thank you. I’m sorry if I’ve been rude. I do appreciate your taking me in, truly. I’ll try not to be a bother. Let me unpack and rest until dinner.” Finally, they left her alone.

Roz put her clothes away, some folded in the armoire, some hung in the closet, a few items left in the trunk at the foot of the bed. Whatever possessed Odette to pack both her wedding gown and her Mardi Gras ball dress in tissue at its bottom? Perhaps, the maid couldn’t bear to leave the costly garments behind on Prytania Street. Whatever, they could stay there in the dark of the trunk, unused and unwanted.

Roz tried to relax but found herself pacing the small room as she had the deck of the ship. She did not want to rest. She wanted to prowl the streets of Chapelle until she came face to face with Pierre Landry.

Chapter Nineteen

Cousin Roz was a bother. She stayed in bed until the family left for Mass and didn’t take any breakfast when she rose. Instead, she dressed and went out, who knew where, meeting them at the bakery after Mass where she declared the beignets to be as good as any in New Orleans. That may have won her approval from Baker Pommier, but dressed in that fancy coat and red hat, how could anyone not know she hadn’t attended Mass? Without telling her friends the whole sordid story, how could Loretta explain Rosamond St. Rochelle?

Roz, herself, seemed unbothered by this quandary. “I went for a long walk. That’s all. After being on the boat, I needed the exercise.”

She’d set out after being quite sure Mass had begun. As she passed the old frame and stucco church of Ste. Jeanne d’Arc with its statue of the martyred saint—another woman no one understood—on its manicured lawn, she wondered if Pierre worshiped inside. Did he come here to pray? Did he attend with his family? Did he go for beignets after Mass? She kept walking.

A block from the Catholic church stood the substantial red brick First Methodist. By the rousing sound of the organ, the service was in full swing. The signboard claimed, “The Methodist Church Welcomes You!” and announced the sermon for today as “Come Unto Me.” Roz never believed in omens but seemed to have come face to face with the real thing. She slipped quietly inside and sat in the very last row to escape notice. Of course, a minister always notices who sits in the last row, especially if they wear a red hat.

When the time came to greet visitors, he urged her to stand and receive the welcome of the congregants beside her and in the row just ahead. She gave her name, indicated she visited relatives, and politely turned down an invitation for coffee, cake, and fellowship following the service.

Roz sat again and marveled at the plain walls free of the Stations of the Cross or statues of saints. She regarded the naked cross above the altar that seemed to say Christ had finished suffering and gone to be with his Father. Though the tall stained glass windows sparkled and the high ceiling of wooden vaults free of gilding were beautiful, she enjoyed the simplicity of the service the most—few rote replies, no mystical Latin phrases, and at least this week, no communion and no need to confess personal sins. Roz swore that even in the last row, she could smell the light scent of burning candles and the fragrance of the altar flowers unobscured by the heaviness of incense.

Reverend Grant took her hand as she left after the service and invited her to worship for the duration of her stay. If he’d known about the mess she’d made of her life, Roz doubted he would be so cordial. He’d probably suggest she give the Baptists a try. Still, she felt lighter than she had in a long time and hungrier, hungry for hot beignets at the bakery across from the Catholic church.

She found Loretta, André, and Henri standing in a long line waiting to purchase a brown paper sack of the square little doughnuts fresh from the vat of boiling lard. Henri dashed from the line to greet her and on the way back to his parents introduced her to his friends.

“These’re my buddies, Teodore Broussard, but we call him Tubbs, and Aldus Thibodeaux. You can call him Boozoo.”

Roz could see how Teodore became Tubbs. The chubby boy steadily made his way through a personal bag of beignets, the powdered sugar drifting down the front of his shirt. Boozoo Thibodeaux was as thin as his friend was fat and looked almost like a cranky old man until he smiled

and elbowed Tubbs to share his doughnuts before they all disappeared down his friend’s throat. Henri tugged on her coat until Roz bent so he could whisper in her ear.

“Tubbs’ grandpa runs the biggest and best speakeasy in Ste. Jeanne Parish. He gives us free root beer when we deliver his hooch to customers. Don’t tell Ma.”

“Henri, come here! It will soon be our turn. Roz, glad you decided to join us,” Loretta called out, but she didn’t seem all that happy.

Roz stood with the family as the line inched forward. The baker’s wife handed another bag to yet another customer. “Bon appetit, Madame Landry.”

Roz stepped from her place. “Excuse me, but are you related to Dr. Pierre Landry?”

“Dere’s lotsa Landrys in Ste. Jeanne Parish. We all related. What you want wit’ him?” the stocky woman in the plain brown dress asked suspiciously.

“We knew each other in New Orleans. He cared for me once.”

“Dat’s our Pierre. He been carin’ for women since Susu Theriot in da eight grade,” replied a lean man wearing his dark Sunday suit and fresh, ironed white shirt. His best hat sat tipped back on a head of iron gray hair the same color as his drooping mustache. Tanned and lined, his face portrayed a life of outdoor work. This was the visage Pierre Landry would wear when he passed fifty.

“You must be his father or a very close relative,” Roz said.

“I’m guilty of dat, oui. Simon Landry, his papa.” Pierre’s father shook her hand and offered Roz a beignet from one of the two large sacks he carried.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

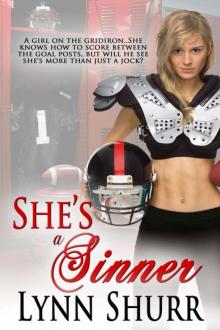

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner