- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Courir De Mardi Gras Page 12

Courir De Mardi Gras Read online

Page 12

Cherry had no major. She switched about every semester. Maybe, she majored in finding a rich husband because she took courses sure to be full of men, a semester of computer science, then sixteen weeks of biology where the pre-meds studied. About the time the grades came out, she’d switch again. Cherry ended up in pre-law. She never got her degree, but she did get her a lawyer.

That man could have been Ghost. He had a habit of wanting to marry every girl he took to bed, all two of them. So, he hauled Miss Bounce-and-Jiggle home to meet Mother. A freakin’ disaster. Virginia Lee served tea and cucumber sandwiches in the parlor, and the girl asked for a Pepsi. Even a black boy knows better than that. You eat what’s served and say thank you in a fancy house like that, at home, too. Mrs. St. Julien tested Cherry on genealogy with the old “I’m descended from George Washington” bit, and Cherry said, “Really? That’s so cool.” At least, the bubblehead knew she failed the interview and announced their breakup while George still tried to figure out what had gone wrong.

Cherry went on to taking engineering classes and dating the ace pitcher of the baseball team. Just as well for her. That year George’s daddy died riding home drunk after the Courir de Mardi Gras. He made the rest of the riders go to Mass, but for the first and last time, the Capitaine stayed on at Joe’s Lounge and got stinking. Coming home, he tried to take a fence on a tired horse in the dark. Real bad judgment there. They found him, neck at a funny angle, all tangled up in his gold and purple cape. His white horse grazed right beside him, reins dangling, ground-tied the way western mounts are trained, a nice help if the man can crawl back into the saddle.

After the funeral, all the worms started coming out of the woodwork at Magnolia Hill. Seems old Jacques did most of his dealing on a handshake and a man’s word. “You bring me fifty dollars cash each month, Rastus, and you can stay in that rat trap I own down in the Hollow as long as you live,” he’d say, or something like that. Should have been as long as he lived.

When old black grannies and decrepit winos started showing up at the kitchen door on the Hill with soiled, wrinkled twenties in their hands, Miss Virginia, a true friend of the poor, started evicting. She wanted everything done proper, down on paper, and collected through her designated agent on Main Street. Those houses in the Hollow stood empty for a long time. During his last term, George needed a scholarship to return to college. You better believe he got it.

The U geared up for another hot season, only George roomed with someone else, which wasn’t his fault. After his daddy died and Cherry took an interest in baseball, George began spending weekends at home after the season ended. But, plenty of girls wanted a piece of Linc St. Julien, and the room stood empty. Doris, being quick, saw the problem at once. With only one more year of school to go, she didn’t plan on losing her man now. By May, Doris had gotten herself pregnant. Okay, Linc got her pregnant, his fault, too.

Now the only thing Linc’s Mama didn’t like about Doris was her religion. Doris came from a family Catholic through and through, her people being descended from St. Julien slaves like Linc’s own daddy and never having seen the light. His Mama said no one ought to listen to that man in Rome, but to pray directly to Jesus like a good Baptist. Whichever way they thought, the answer came out the same. Doris said no abortion. Linc’s Mama said listen to Jesus. Their wedding took place in June.

As newlyweds, they lived in Port Jefferson that summer. George stayed down in the Hollow a lot, trying to fix up his mother’s rent places, but Port Jefferson isn’t New York City. No one liked or trusted Virginia Lee. She got no takers on the property. George hung out at Linc’s mama’s house, spending plenty of time on the screen porch, eating yam pie, and drinking iced mint tea. Doris stayed trim and pretty during those first months, and the newlyweds had a perpetual summer honeymoon going on.

George liked their company, but he stayed in the Hollow for a purpose. Not to say he used people, but he used his brains. He had some of those rent houses filled by September. Papers had to be signed, and the rents went higher for the improved property, but he sealed the deal with a handshake. George asked Linc’s Mama to act as his rental agent until he could graduate.

In the fall, Mr. and Mrs. Linc St. Julien got a little apartment of their own near the university, and George found a new roommate. Agents came waving big money around, tempting the big star forward to quit school and sign a contract with one of the NBA teams. But, Mama, the school teacher, said, “No way.” That college diploma might mean everything some day. Her son would play out his senior year.

Doris picked basketball season to really pop out. She came to every game and sat in front looking like she had stole the ball and hid it under that stretchy pink top she sewed herself. The guys razzed Linc a little about Doris until they saw it threw his game off. Then, they let up, but the opposing teams caught on and said things that pissed him off so bad he couldn’t see straight to shoot.

The Ghost, though, just kept feeding Linc the ball nice and regular until he got him settled down. Wasn’t the best year, but the U made it to the regional championships, only not the Final Four this time around. That showed come draft pick time. Linc St. Julien didn’t go as anybody’s first pick, but he got a good enough offer to step up to the big leagues. He didn’t blame the baby either for not getting a better placement. When little Tiffany came with her milk chocolate skin, big brown eyes, and velvet hair, her daddy wanted to make it as a star more than ever.

George “Ghost” St. Julien had some good offers, too. When Linc left for training, he wanted to say to his friend, “May all your troubles be little ones like Tiffany,” but knew they wouldn’t be. George turned down the contracts and went back to Port Jefferson to see his mother through the first of her leukemia treatments because she begged him to do it. He passed the CPA exams and set up his office in one of the family’s rent buildings on Main Street. Virginia Lee decorated the place. He checked in with his rental agent about the problems she noted on houses in the Hollow and told her she had done a fine job, but he would be collecting the rents himself now. Without saying it, Odette St. Julien knew the people at the Hill could not afford her agent’s fee anymore. Strange times when the rich become poor.

Old Jacques never had a sick day in his life and didn’t believe in health insurance. Hell, he had wealth and good luck. And, he died early and easy. George carried the insurance the athletes were required to take, but that didn’t cover his mama. She wasn’t old enough for Medicare and way too proud for Medicaid. They would have had to sell the Hill and declare bankruptcy to get it, anyhow. Virginia Lee lingered on and on.

Being men, George and Linc didn’t keep in touch much except for the phone call about the bombshell Doris dropped at Tiffany’s first birthday party when she said, “And Mama’s giving you a new baby brother or sister in about seven months.” Doris found that a cute way of telling her husband. No way was Linc ready for another child. But when Crystal came along so tiny and delicate compared to Tiffy who, truth be told, had big bones like her daddy, he couldn’t blame that child either.

Linc blamed himself that his career didn’t go as well as it should. Now, Linc St. Julien was just one big man among a hundred big men. Lots of times he didn’t start a game. Lots of times, he didn’t get in a game. But when he went back to Port Jefferson and sat sipping a brew on the porch with George, he knew he had no troubles at all compared to his friend.

It seemed like George was turning gray, oh, not along the scalp line, but in his personality. Say “How about a little one-on-one.” And he’d answer, “I’m not in your league anymore, Linc, old buddy,” and have one too many beers. Linc’s mama said George came to shoot baskets alone at the tattered hoop screwed to their garage, one ringer after another until little boys began to keep count. He’d give them a few pointers, and then go back alone to the Hill and his sick mother.

George took to slicking back his hair like his daddy used to with cream stuff. He even used the same cologne. Old Spice, maybe. Could be he thought this

would remind his clients of the kinship or his renters of their lease, but it didn’t help his looks any. Maybe George’s old lady mother was trying to make her son over into a man like his daddy, but one she could control. Couldn’t say anyone in the Hollow grieved when Virginia Lee died, though Odette St. Julien said everyone should pray for her soul.

By then, Linc came back to Port Jefferson for good. About the time Doris told him—this time there was nothing cute about it—that their number three daughter was on the way, he began feeling a little desperate. He made good money, but not great money, and keeping up the life style in a big city sure took its share. The signing bonus dribbled away, and his investments could only be called limited.

He asked George to find him some land in the country for his retirement. That much got bought and paid for. George served as his agent locally, but no one offered any big endorsements for a second-string player. Working hard on his game that year, Linc got it together. “Most Improved Player” they called Linc St. Julien. The next year, he started for the team, and Doris started on giving him a son, Little Linc. But, his knees didn’t last. He blew out one, then the other—another career down the crapper.

That PE diploma his mama insisted on came in handy when the great basketball star had to go over to Port Jefferson High and beg for a job. He got on as a gym teacher and assistant basketball coach, glad to have the work. Not too much later, the high school made him head basketball coach. Lucky, and luckier to have George St. Julien as his friend, too. George saw to it that a brick house in the country got built with the last of the NBA contract money. He might have put in a word at the school board office, but he wouldn’t tell if he did. Most of all, George never mentioned Linc’s last big game except to say, “Tough break about the knees, but it’s good to have you home again.”

He owed George for that and for saying “if it’s okay with the gentleman,” freshman year. He owed the man for never razzing about Doris and her yen for motherhood. He owed his bro for all the basketballs he handed off to the star to dunk and dazzle the scouts in the stands. Linc owed George and wanted to do something for him. That’s why he butted in when he got his mama’s call, her all excited.

“Did you meet the nice girl working for George at the Hill?”

“No, Mama.”

“Well, she’s just right for him,” his mama went on. “And maybe George hasn’t noticed that yet.”

Linc stopped her right there. Mama’s definition of a “nice girl” was any polite female who went to church regularly, not George’s type at all. He liked those wild women.

“I’ll check her out, Mama,” he promised. “But I don’t think….”

“I know what you think, Mr. Abraham Lincoln St. Julien. You think she’s fat or ugly. Well, she isn’t. She’s nice looking, bright, and has a mind of her own, or I never would have met her. Now you just work on George. He might need a little help on this one, and he isn’t getting any younger.”

Linc gave up. “Yes, Mama.”

****

Naturally, Doris thought fixing George up was a great idea. She thought everyone should be married and have four kids. She wanted to invite the both of them to Sunday dinner, but George needed to be sounded out first. He hadn’t said a word about this girl as they watched the game the night before.

The two of them sat on the patio having a drink before dinner. The kids played on the gym set, and Doris fried up that special chicken of hers. Linc brought the subject around to women, and they talked about their old college days.

“I hear Cherry married a New Orleans lawyer, but sleeps with a pro football player. LaDonna doesn’t have the energy to do it anymore since she had the twins, or so she tells my mama. Good thing you got away from them both, Ghost, my man.”

“Yeah,” George said like he didn’t agree.

“Hear you got a good looking woman staying up at the Hill right now. Anything happening?”

“Nope.” George nursed his beer and looked away. Right then, Linc knew there was something in what his mama said.

“You never had any trouble finding women in the good old days, Ghost.”

“Everybody loves a sports hero, Linc.”

“You’re the same fine dude you always was, man.”

George belched for an answer.

“So when you’re not a hero, you just have to put a little more effort in it. Do something romantic. And Gawd, get your hair fixed.”

“My dad did just fine with his hair this way.”

“You’re not your daddy.”

“Don’t I know it? You should see the way Miss Suzanne Hudson ate up that portrait of my old man on his white horse. I hate horses.”

“But you can ride, can’t you? All you rich kids learn to ride.”

“Yeah. I learned to ride on this nasty, little sonofabitch pony my dad picked out especially for me. My feet practically dragged on the ground. I went over that boneheaded bastard’s head so many times I thought it was the only way to dismount.”

“Take her riding if she’s into mounted men.”

“It’s not just the horse. It’s the cape, the hat, the eyes, the leer, the whole goddamn style of that kind of man. I haven’t got it.”

“So get it.”

“It’s not for sale, and I couldn’t afford it even if it was.”

“I don’t know about that. Look, try the obvious stuff first. Have lunch together. Invite her out to dinner. Try dancing. If that doesn’t work, I have a plan.”

Doris sent George home with some fried chicken and yam pie for his “friend.” No surprise that the obvious didn’t work because George had no confidence in himself anymore when it came to women. Seven years of nursing the ice queen had seen to that. He called saying his spontaneous arrival home for lunch with hot French bread hadn’t worked out too well.

“Yeah, right. Nothing says romance like bread, George.”

“She was upset over a letter in the mail.”

“From a man?”

“I guess. I don’t know.”

“Great! She’s on the rebound. You were always the best with the rebounds, George. Did you ask her out?”

“I was going to. I will.”

“Look, it wouldn’t hurt to tell her some of your problems without getting too wimpy. Women love to dish out sympathy.”

“I don’t think I can do that.”

“Then, we’d better work on my plan. Mardi Gras is coming up. You go into the city to one of those big costume places and get yourself a cape, a plumed hat, the whole bit. I’ll work on the white horse, one you won’t be afraid to ride.”

“This is ridiculous, Linc.”

“If they want to be carried off on a white horse, then carry them off on a white horse. No wonder I was the one who always had to call the shots. You have no imagination, George.”

“I’ll feel like a fool.”

“So long as you don’t act like one. Now get on it!”

“Right, Coach!”

****

George loosened up the next few days, especially after the brawl at Joe’s Lounge. He didn’t look like a man who kept in shape because he nearly always wore a suit that sort of hid his physique. He had that long kind of muscle, not the type that gets bulky. Linc and George, the two of them worked out with the weights and played ball as often as they drank beer at Linc’s house. The strength of George’s right arm must have come as a real shock to the Patout boys. How cool it would have been to see those rednecks pee in their pants, but blacks knew to stay out of Joe’s Lounge. Still, getting drunk and flattening three Patouts probably did not improve George any in Suzanne Hudson’s amber eyes. Passing out from a bad wound might, but passing out drunk had never been high on Doris’ list of romantic ways to end an evening. Suzanne probably felt the same.

Plans moved ahead. George got the costume, a real beauty, all black with just a red cape lining. The costumer called it the Devil’s Horseman model and altered it for George’s length free of charge since he would be buying, not

renting. The Ghost looked fantastic in that outfit except where the frame of his glasses showed above the black satin mask.

“Take off the specs, George.”

“I won’t be able to see.”

“Whatever happened to those contacts you wore when we played ball, the ones with the blue tint that drove the women wild?”

“In my dresser, I guess. Mother said I didn’t look like her son with those things in my eyes. I guess they were a little bizarre.”

“Find them, or get another pair.”

He tried to argue, but Doris barged into the garage just then to get Misty’s bicycle. She gasped and put a hand to her throat, then relaxed. “Oh, George, if I hadn’t seen those glasses I wouldn’t have known it was you. You look so dashing. Getting ready to take Suzanne to Mardi Gras?”

Then, she turned on her husband. “Why don’t we ever go to Mardi Gras anymore?”

Part Two of the plan was thought up right then—the part that turned out to be such a bad idea.

“Sure, baby. Why not? Can you make me a pirate costume?”

“Not like that. That’s professional sewing,” Doris said fingering George’s cape like she could hardly keep her hands off him. “Would you just look at this heavy scarlet lining? I like the way they sewed on the braid to cover the seam when they lengthened the arms and legs. Very nice—like something you’d see at one of those fancy masked balls they have in New Orleans.”

“No, no, honey, I don’t need anything like that. I’ll just put on some jeans and a tight striped shirt. You make me a mask out of a bandanna, and I’ll wear one of my gold earrings from back in the days before I became a teacher. We can dress the whole family up the same way and take in the parades in Lafayette.”

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

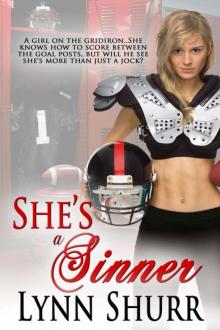

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner