- Home

- Lynn Shurr

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Page 10

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Read online

Page 10

The pattern continued for the next five weeks: family gatherings on the weekends, church on Saturday or Sunday and sex on the sly which made it all the more delectable. Nadine soon caught on and suggested Joe’s daddy could use some help on the farm because he wasn’t getting any younger. She rousted Joe out at dawn before the heat of the day got too bad. He came home covered with sweat and grit, the edge taken off his boundless energy.

“Hard exercise,” Nadine confided to Nell, “is what boys need to keep themselves in control. That’s what sports are for. That’s why Joe got so good at football.”

Nell helped around the house when Joe was gone, offered to cook occasionally and usually ended up taking lessons on how to make Joe’s favorite foods. At one point, Nadine, while supervising her roux-making, actually said, “Lovin’ don’t last, good cookin’ do,” a favorite saying from her grandfather. All of this did not stop the lovemaking, even if it meant climbing out of windows at night and taking off with a blanket from the bed for the cane fields. Afterward, Nell stayed awake wondering why she could not get enough of Joe Dean Billodeaux.

An old-fashioned Fourth of July celebration came and went with ancient veterans marching down Main Street, a concert given in the square by the community band and sky rockets over the bayou. Lizzie’s husband, Charlie, bought a fortune in fireworks and the family went to their house to set them off. The shabbiness of the place didn’t show up too badly at night. Lizzie told Nell she waited for the day when her sons could paint and do a good job of mowing the lawn, but tonight—tonight was fine.

The other men made Joe and Charlie sit on the sidelines and watch because, they said, Joe couldn’t risk his fingers and Charlie’s breath might set off an explosion. Charlie, too drunk to care, slung an arm around Joe’s shoulder and cheered at the brilliant lights like a child. His famous brother-in-law, seated, kept the tippler out of harm’s way. A caring family taking action without spoiling the fun or embarrassing Lizzie, Nell analyzed before she could stop herself.

All the children but the babies were allowed to have sparklers, and they played writing their names in streaks of golden sparks or green smoke. The teens shot off bottle rockets until some of the boys started aiming them at each other and Nadine ended that. Finally, Allie’s husband, who had already lost a finger out on the rigs so it wouldn’t make any difference if he lost another, set off the grand finale of Patriotic Salutes, Angry Alligators, Swimming Fish, and One Bad Mothers that popped and sizzled over the cane fields. When the concussion ended, the tree frogs took a full five minutes before they felt they could resume peeping.

On the way home, Joe executed a successful escape from the family down a side road and made love to Nell in his old double sleeping bag rolled out over padding in the long bed of his new silver truck. Afterward, he and Nell watched for shooting stars, made their wishes and kept them secret from each other.

Tired of being separated for most of the days, Joe woke Nell at dawn one morning, packed a double lunch and took her out to the plantation for a ride in the high glass cab of the cane tractor. They rolled along the rows on man-high tires in air-conditioned comfort, the cane swishing under their seats.

“My daddy, Uncle Wylie and Uncle Ross went deep into debt for this farm equipment. With Wylie’s diabetes and Ross having high blood pressure, they thought the time had come to add comfort, and maybe some years to their lives. I paid off the balance owed last year and they forced me into taking shares in the plantation. When the old men pass on, I plan to give my shares to Eenie’s husband because I sure as hell do not want to farm cane.”

“You are a better man than you let people know, Joe.”

He shrugged. “They’re family.”

Nell caught on to driving the tractor easily. Compared to riding a horse, this was no problem at all. One afternoon, having left Frank under the single, wide oak in the center of a field to take a break, Joe and Nell rolled off in the massive machine and were gone more than an hour. Joe’s daddy, still sipping hot coffee from the cup of his thermos when they returned, gave them such a look Nell felt compelled to check her buttons and Joe glanced down at his fly to make sure he was zipped.

The next day, Frank suggested Nell stay at the house and help out Mama who wanted to jar some okra. Allie came over to help because Eenie was working part-time at the Wal-Mart now that her girls were old enough to stay alone. She and Darryl needed the second income. Izzy sat at the kitchen table with her swollen ankles propped up on a chair and helped Nell cut the fuzzy green pods into seedy circles. The last of the home-grown tomatoes dipped in hot water also fell to Nell to peel and dice. They’d do some of the okra with tomatoes the way Frank and Joe liked, then pickle the rest whole, Nadine decided.

The second batch of steaming jars was coming out of the hot water bath when Nell’s cell phone rang from the bedroom. Washing okra slime and tomato seeds from her hands with a quick spurt of the kitchen faucet, Nell dashed to catch the call but arrived in time only to receive a voice mail message. Joe Brunner informed her that one of her patients had died. The funeral was tomorrow at eleven in New Orleans, at Bultman’s, if she could make it. When Nell failed to return to her chopping duties, Izzy heaved herself up and went to find her crying on the bed. One by one, the women came from the kitchen and clustered around Nell, patting and consoling. Joe found all of them in Allie’s old bedroom when he came in from the fields.

“Let me take care of her,” he told his mama and sisters. Reluctantly, they went back to the neglected canning. Nell made his sweat-damp shirt wetter when he took her on to his lap.

“You expected this to happen if the transplant didn’t come through in time.” Joe kissed the top of her head.

“I know, but I wasn’t there for the child or his family.”

“We’ll drive into the city for the funeral. Then, I was thinking we could pick up Cassie and some of her brothers and sisters and bring them to see the ranch. Bijou says the ponies arrived late yesterday. We haven’t been out to see them. We could cook up some hot dogs and hamburgers, easy stuff. We can’t do anything for the other little guy, but Cassie might like some company.”

“That would be good.” Nell kept her face pressed against his chest. He eased back against the old maple headboard and stretched out his legs on the white eyelet spread. Letting Nell rest against him, Joe rubbed her back until she slept.

When his mama checked on them a few minutes later, she nodded and mouthed to her son, “Good boy, Joe.”

Cerise and purple crepe myrtles brightened the Garden District and pink banana blossoms, glorying in the heat and humidity, topped the walls, but the air inside Bultman’s Funeral Home stayed chilled and redolent with the fragrance of hothouse carnations and lilies. Christopher’s family had money and prestige enough to guarantee many bouquets and a large attendance of mourners, but no amount of either had gotten their son the heart transplant he needed so urgently. Joe, shivering in the sudden cold, cringed at the thought. Money and fame couldn’t make everything right in the world.

Nell apologized to the family for being away when the crisis had come. Christopher’s blonde, stylish and totally devastated mother answered saying, “There was nothing you could have done, but thank you for coming.”

Nell pressed one of her cards into the mother’s hand. “Call my cell if you want to talk or if I can help in any way.”

Christopher’s father took the card from his wife’s damp palm and put it in the pocket of his dark suit. He shook Joe’s hand. “Joe Dean Billodeaux. I don’t know how you knew about my son, but thank you for being here. We went to some of the games together when Chris was well enough, watched them on television when he wasn’t. I bought two tickets for the opener in the Dome.” The father turned his head away, fumbled with a handkerchief he tried to conceal, wiped his eyes and turned back to Joe. “Thanks for coming.”

Joe and Nell took seats for the brief service about a short life. Most of the funerals he’d attended had been for relatives who died of the

diseases of old age except for the teenage cousin killed in a car wreck. That last one that been awful. This, the funeral of a child, was worse. He wouldn’t be here if not for Nell’s sake.

He breathed easier when they went out in the heat again and headed for Cassie’s home in a much less fashionable section of the city. Passing from the Garden District through areas devastated by Hurricane Katrina, he wondered if he had done enough to help. Sure, he’d donated money, even slung a hammer to put up a few houses when the Rev asked him to help, but he had so much and what did he do with it—build a mansion, buy cars and chase women. The drive made him almost as uncomfortable as the funeral.

Following telephone directions, they found the address posted on what looked like an old boarding house, big and square with no frills on the porch. A gray van that had lost most of the shine on its finish sat parked outside.

As soon as the Porsche pulled up, redheaded children began pushing out of the front door. Cassie stood out as tallest of the bunch. Short auburn curls covered her head in a style that seemed almost intentional. She’d been experimenting with blue eye shadow, mascara and goop to cover her freckles. Nell’s patient had become lanky with a sudden growth spurt and her breasts were an unlikely size in what Joe decided was a very padded bra.

“Miss Nell, Mr. Joe! These are my younger brothers and sisters.” She pointed to each redhead. “Ben and Brian and Bridget and Nora and Kathy. Don’t we look like the Weasleys?”

Joe drew a blank. He looked at Nell.

“From Harry Potter,” she whispered.

“Sure do,” Joe answered, still having not the slightest idea.

“Bonnie has a summer job, the oldest four are in the service trying to earn money for college and Dad had a chance at overtime, so it’s just us who will be going.”

Small hands left fingerprints on the gleaming red hood of the Porsche. Joe didn’t say a word. Mrs. Thomas came from the house carrying a huge plastic jug of red punch and a large brown paper grocery bag.

“Snacks for the trip. Peanut butter sandwiches. It’s such a long drive. I can follow you in the van. Get in, children! The house is such a mess, or I’d invite you in. Cassie gets the front seat. No complaining. You wouldn’t be going if it weren’t for her. Don’t argue with your mother.”

“Mom, I want to go in the sports car with Joe!”

“I’d be happy to ride with you, Mrs. Thomas. I can pour the juice as needed,” Nell offered. Looking a little flummoxed, Joe agreed to a change of passengers.

He led the caravan the shortest way to Chapelle. They stopped once at a gas station when the twelve-year-old van overheated. The children lined up for the bathroom while Joe waited for the radiator to cool before adding water and antifreeze. Nell came to stand beside him while Mrs. Thomas supervised the bathroom brigade. They watched the steam rise from the engine.

“How are you doing with Cassie in the shotgun seat?”

“Fine, except for going deaf in my right ear from the chatter. She’s put out that I didn’t invite Connor, but hey, he and Stevie are still honeymooning. It’s only a week or so before training camp. They need their time alone. At least, that’s what Stevie told me the last time I barged in on them. The Rev is coming. I gave Bijou the keys to the truck so he could go on over to Versailles and pick up the big grill since mine isn’t ready yet. I hope they let him in. How about you and the redheaded gang?”

“It’s great to be around a family with so much energy, sort of like yours.”

“You don’t find my family—overwhelming?”

“Yes and no. They’re good people, Joe.”

“I think so. Funny, isn’t it, how many kids Mrs. Thomas has and hers gets well. Christopher, he was an only child, right?”

“Yes, born with a severe congenital heart defect. They did what they could with surgery, but it wasn’t enough. His mother was afraid to have more children. I can assure you, though, if it had been Cassie in that casket, the grief would have been just as severe.”

“I know, but sometimes life isn’t fair.” Joe reached over, removed the loosened radiator cap with a rag and fed fluids to the ailing van.

“There are no referees to call a foul and make things right, Joe. I figured that out a long time ago.”

Joe hugged her to his side and leaned to place a kiss on her cheek.

“Hey, break it up! That’s my counselor you’re mauling.” Cassie had returned. Red-haired Thomases surrounded the old van like a Celtic hoard ready to attack. They loaded up and moved out toward Chapelle.

The ponies, one fat and spotted, the other shaggy and palomino, won the hearts of the children merely by mooching sugar cubes from small, open hands. They answered, more or less, to the names Boo and Buttercup and wore spiffy tack in red and blue leather. For Shetlands, they were very good-natured. The younger Thomas children rode the animals into exhaustion, going round and round the dirt practice ring that had materialized from the scrub and rotting posts on the far side of the barn where an old Cajun racing track once stood.

Leaning against the new, white-painted rails, Joe told Nell, “In my grandfather’s day, the men would come to bet cash on match races on the two-lane course and maybe fight cocks in the barn. Big tracks like Evangeline Downs and people disapprovin’ of cock fighting put an end to all that at Lorena Ranch. They still raise game cocks all over the parish and supposedly ship elsewhere to fight.”

“You’d never fight chickens, would you?”

“How stupid would I be to get caught doing something like that when I have almost everything I want in life?”

Nell started to ask what else he needed when Boo decided he’d enough and stopped dead, allowing Brian to slip over the pony’s head and end up a heap in the dirt.

“Get up, get on and show him who’s boss,” Joe prompted the boy.

Brian dusted himself off and remounted determined not to lose his turn, no harm done at all. Cassie flew by on Fatima. One lesson with Joe behind her in the saddle and she rode like an Indian.

“How come you put me up alone on that huge animal and Cassie gets the babe in arms treatment?” Nell had to ask.

“Since you are always trying to impress on me how tough and fierce you are, maybe I didn’t want to insult you by implying you might need help.”

“I did.”

“Still do.”

Bijou, who had dressed up for company in a clean western shirt with a red rose embroidered on the pocket and pearl snaps down the front, took a place on the other side of Nell, removed his snuff can from a worn jeans pocket and filled his lip with smokeless tobacco. Five assorted rings sparkled on his blunt fingers.

“She’s a natural, that Cassie. Look at her go. Probably, I could train her to be a barrel racer, win some prizes.”

“She lives in the city, Bijou, and is supposed to start at a Catholic girls’ school at the end of August. Her mother got her a scholarship. I don’t think she’ll be doing much barrel racing.”

“Just sayin’. Girl has spirit.” Bijou spat on the ground. Nell moved her feet.

Mrs. Thomas came around the barn and called out the food was ready. Her younger girls, who had finished riding, placed plastic knives and forks on red-checkered table cloths covering the plywood and sawhorses forming a long table. Green resin stack chairs surrounded the table. The Rev flipped over hamburgers and got ready to fork hotdogs on to a plate. He had declined a chance to ride by saying he didn’t like the look in the eyes of the big red horse and he couldn’t afford no broken bones just before training camp.

Nadine arrived with a trunk full of potato chips plus enough crock pots full of baked beans to feed the Confederate army. A long, green-striped watermelon floated in the ice and water of a large cooler along with bobbing cans of cold drinks. Dinner was served.

Nell, stuffing hot dogs into buns, felt herself falling in love with Joe Dean Billodeaux, his large and generous family and his enormous, warm-hearted friends. That simply could not happen. This was supposed to be fun, a summer

romance. Nothing more could be allowed.

The Thomas family departed around eight with Cassie’s mother turning down an offer to be followed by Joe. “I’m used to this cranky old van. We’ll be fine.” Nevertheless, Nell scribbled her cell phone number on a napkin and gave it to Mrs. Thomas.

Cassie had to be routed from the barn where she was saying good-bye to the horses. “Bijou says if I can come over more often, he’ll show me how to barrel race once I get a better seat. He says I have the build for it.”

“You call him Mr. Bijou, Cassie,” her mother said. “We have no money for riding lessons.”

“He won’t charge. I can drive up here alone once I get my license.”

“You told her to get involved in things, Nell. What does she choose? A driver’s ed class, and she won’t be sixteen until September.” Mrs. Thomas rolled her eyes. “I didn’t have the heart to turn her down.”

“Can I drive on the way home? I wanted Joe to let me drive the Porsche, but he said I don’t know standard. I could learn though. Bijou says I’m a quick learner.”

“Mr. Joe, Mr. Bijou,” her mother corrected again. “Thank them for the nice day.”

“Already did. Nell, I passed my written exam last week and already have my permit. I could come here to visit you as soon as I get my license in September.”

“Cassie, I won’t be here in September, but you can visit me in Metairie.”

Joe stood behind Nell, his hand resting on her narrow shoulder. His fingers clenched for a moment. He removed his hand to wave to the red-haired Thomases as Cassie took the wheel and pointed the van down the lane after backing up in a large half-circle.

Nadine packed the dirty crock pots and half full bags of chips in the trunk of her car. The Rev and Bijou maneuvered the grill on to the bed of the Silverado. Nell went to fold the tablecloths and stack the resin chairs. Mrs. Thomas had made sure her children picked up the trash and bagged it in two black plastic trash bags before leaving. Joe drained the cooler and placed it on the back seat of his mother’s Honda.

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner

Sinners Football 02- Wish for a Sinner Sister of a Sinner

Sister of a Sinner Courir De Mardi Gras

Courir De Mardi Gras Mardi Gras Madness

Mardi Gras Madness Paradise for a Sinner

Paradise for a Sinner Putty in Her Hands

Putty in Her Hands Son of a Sinner

Son of a Sinner Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball

Queen of the Mardi Gras Ball Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances)

Love Letter for a Sinner (The Sinners sports romances) A Wild Red Rose

A Wild Red Rose Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner

Sinners Football 01- Goals for a Sinner The Convent Rose (The Roses)

The Convent Rose (The Roses) Kicks for a Sinner S3

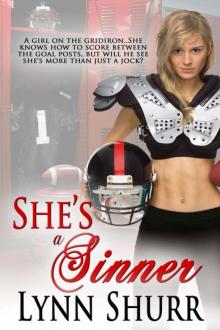

Kicks for a Sinner S3 She's a Sinner

She's a Sinner